Transcript

Interviewer: Greetings! What is your name?

Manu Chitrakar: My name is Manu Chitrakar.

Interviewer: How long have you been living here?

Manu Chitrakar: I was born and brought up here.

Interviewer: Who was the eldest member in your family?

Manu Chitrakar: My father.

Interviewer: When did your father settle down here? How long has it been?

Manu Chitrakar: It is more than ten years since my father passed away. So, he had lived here for around fifty years.

Interviewer: Have you been living here since your childhood?

Manu Chitrakar: Yes, since my childhood.

Interviewer: Where did your forefathers, I mean, your grandfather, live?

Manu Chitrakar: They were from Thekuachawk, Purba Medinipur.

Interviewer: Have most of the patua families migrated from Purba Medinipur? Or is it vice versa?

Manu Chitrakar: No. Patua families from Purba Medinipur have migrated to this place. Hundred years ago, there was no patua community here in Naya. So, it has been a hundred years since the community settled down here.

Interviewer: Who were the first people to have settled down here?

Manu Chitrakar: The first person to have migrated here was Jyoti Chitrakar’s grandfather. I can’t recall his name. Then eventually, they all came and settled down here.

Interviewer: When you were young, how many families were involved in patachitra? Has there been any change since then? Has the number increased or decreased?

Manu Chitrakar: The number has increased. Initially, there were just three families. They used to roam about villages displaying patas. They used to put up temporarily at this place and then go around several places along with their paintings. That is how they gradually established a permanent settlement here.

Interviewer: Are all the families living here, patuas? Have they been practising patachitra for generations? Or did they start practising this only after moving to Naya?

Manu Chitrakar: These are all patua families. But the fact is that we get more customers here and our sales have increased after we came to Naya. That is why patuas from other regions have come and settled down here. The scenario has improved since the last twenty years.

Interviewer: Back in those days when you were young, what usually were the themes of patachitra?

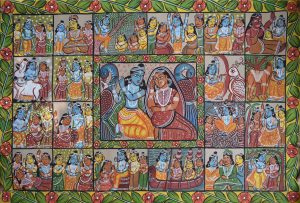

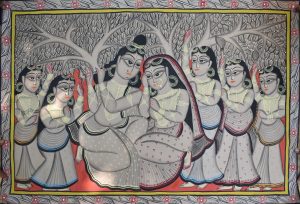

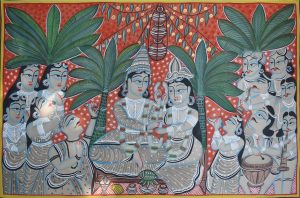

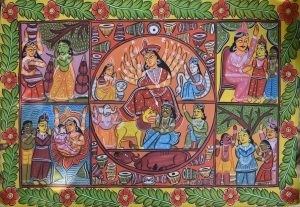

Manu Chitrakar: Patachitras, back then, were usually based on the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. There were just two patas that were based on contemporary social events. One was on violence against women and the other was on the Independence Day. The others were all based on mythological stories.

Interviewer: Are you still able to continue with the tradition of painting patas based on mythological stories? How?

Manu Chitrakar: The mythological ones – the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, the abduction of Sita, Mangal Kavya, Chandi Mangal have been handed down to us by our predecessors. So, we have maintained that tradition. Simultaneously, we also bring to light certain events that are taking place across the country. For instance, if there’s a problem in Gujarat, West Bengal, or perhaps Uttar Pradesh, we try portraying that through our patachitra and spread awareness so that everyone can live peacefully.

Interviewer: How did your father and his generation earn their livelihood?

Manu Chitrakar: They used to roam about villages displaying patachitras. These patachitras were not meant for sale. They were mainly for display. They were often displayed during religious ceremonies in zamindar family homes. But nowadays, they are mainly for sale and sometimes for creating awareness.

Interviewer: Since when did you start selling patas? When did you realise that this could become your means of livelihood?

Manu Chitrakar: Maybe for the last thirty years.

Interviewer: Did you get any help from anyone or any organisation in your endeavour to create a market for patachitra?

Manu Chitrakar: Of course. There was a time when, with the advent of television, patachitra gradually got relegated to the margin. It was no longer considered a viable form of entertainment. The condition of patachitra was pitiable. But some people from Kolkata who loved painting came to Naya to carry out their research. These people then started highlighting this art form. They used to buy patas from us. They also recommended our names to various art galleries. Our sales started increasing only because of these people from Kolkata.

Interviewer: Which kind of patachitra is usually preferred by customers? Are you adapting this art form to their preferences?

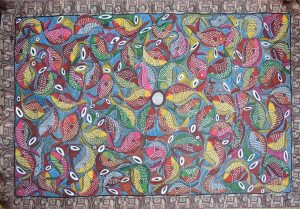

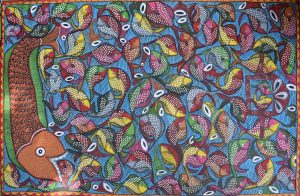

Manu Chitrakar: No, the genre isn’t getting completely transformed. The stories are getting altered. The patachitras based on mythological stories have, however, remained the same. But now we are working on new topics like the depletion of mangrove forests, water pollution, etc. We paint on topics that we want to. But then patas are customisable as well.

Interviewer: Are customers still attracted towards patas based on mythological stories?

Manu Chitrakar: Yes. The appeal of the mythological patas has remained unabated. Let me explain why I’m saying this. Whenever we sing a pata song on a certain social issue, it is always followed by requests to sing on mythological stories. People request us to sing on the Ramayana, the Manasa Mangal. So, there is a continuous engagement with these epics.

Interviewer: How is the length of a pata decided? What are the factors that come into play?

Manu Chitrakar: Once a song is composed, the number of scenes required to depict it gets decided. Therefore, we decide how long a scroll should run.

Interviewer: Does the price of a scroll depend on the length of the scroll or is it determined by the quality of the work?

Manu Chitrakar: These are completely two different things. Deciding the price is one thing, whereas, deciding the length of the pata is another – it is a personal choice. It is true that we often make shorter patas for someone who pays us less. But then we also get requests from customers specifying details of the size they want. When we paint scrolls completely out of our own will, we do not worry about the question of money. A pata is as long as its narration requires it to be. Again, there are times when we fix the price according to the length and breadth of the scroll but then realise that we won’t be able to find customers for such a high price. We are then compelled to sell it for a much lower price.

Interview:Which one is preferred by customers – the long scrolls or the small square ones?

Manu Chitrakar: At present, the sale of small square patas is higher. Scrolls are bought by museums and art galleries, or maybe for a special occasion. Otherwise, small patas are more in demand.

Interviewer: Were the earlier patas based on mythological much longer in size?

Manu Chitrakar: Yes, there were longer. Earlier, patachitra was meant mainly for singing. Each pata song spans fifteen-twenty minutes. The scroll was, therefore, made accordingly. But now, the purpose of patachitra has changed. It is put up for sale. So, the measurement of the space available, ultimately determines the length of the scroll. It would be difficult to hang a scroll that is too long.

Interviewer: How much change have the pata songs undergone?

Manu Chitrakar: The songs have changed a lot. The tune has undergone a change. Tunes of other songs, especially tribal songs from remote places are often used.

Interviewer: What about the lyrics? Have they changed as well? How different are the lyrics now from those that you had heard during your childhood?

Manu Chitrakar: The lyrics, too, have changed. Earlier the songs were composed in the same colloquial language that we conversed. But now, since the patas are being displayed at so many places, the colloquial language is gradually getting replaced by the one spoken in Kolkata. A richer vocabulary has replaced the earlier lyrics. It has basically undergone drastic changes.

Interviewer: You just mentioned that a lot of patas are being made on contemporary social issues. Are you composing new songs on these new topics?

Manu Chitrakar: Yes. The mythological ones have the same songs. But the new patas created on social issues have new songs accompanying them.

Interviewer: Can everyone out here compose songs? Have you received any training to serve that purpose? Or are there few selected people who are capable of composing songs?

Manu Chitrakar: Actually there are only a handful of patuas who can compose songs. We don’t have too many people who can do this. Some patuas compose songs and others also sing them. We compose songs ourselves as well. We reflect upon the topic and decide on how it could possibly be depicted. We do not always require help for that. I have seen my father compose songs and that is how I have learnt to do it.

Interviewer: What about the next generation? How do you think you can inspire them to take up patachitra? Do you earnestly want them to follow the tradition? Is there an implicit pressure on these kids?

Manu Chitrakar: We definitely want them to carry forward this tradition. That is how patachitra will survive. At the same time, the young generation is also witnessing how patuas are travelling far and wide because of this. They are also enthusiastic and keen. They know that it’s not possible to visit America on your own expenses. But if they remain associated with patachitra, someday they’ll perhaps be invited over. That is a ray of hope for the young generation.

Interviewer: Nowadays, children are getting educated. What if they were to choose a different occupation? What would be your opinion on that?

Manu Chitrakar: If someone wishes to choose a different occupation, we are fine with it. But obviously, we’ll feel good if the tradition can be maintained. There was a time when people left patachitra and started taking up other professions. But now, they are coming back again to pursue patachitra. The young generation is extremely enthusiastic about this art form.

Interviewer: Are you all followers of the Islamic faith? Or do you have people from other religious communities as well?

Manu Chitrakar: Patuas from this village are all Muslims. You’d find quite a few Hindu patuas in Birbhum. Again, in Purba Medinipur, there are both Hindu and Muslim patuas. But just because we are Muslims, we do not necessarily confine ourselves to Muslim artworks. Likewise, the Hindus also do not restrict themselves to only Hindu images. On the contrary, the very fact that we paint images of Hindu deities, despite our Muslim faith, speaks of communal harmony – a harmony which we try to maintain through patachitra. When there are sparks of communal animosity, we try painting patachitras and expounding on the need for communal harmony. This is something that we do completely out of our own volition. No one dictates to us what should be done.

Interviewer: Let’s talk about the way patuas are named. All the patuas have the same surname -‘Chitrakar’. It is difficult to guess one’s religious identity from a patua’s name. What is the story behind this? For instance, your name is Manu (which sounds like a Hindu name), whereas your brother’s name is Anwar (which is a distinctly Muslim name). Why is this so?

Manu Chitrakar: There was a time when a patua had two names – a Hindu and a Muslim name. Earlier, we used to roam about villages singing pata songs. So, when a village with a Muslim population would be visited, the Gaji Pir’s song would be sung. On such occasions, the Muslim name would be used. But when we would visit a Hindu household to sing a Durga pata, we would use our Hindu name. We behaved so in order to receive generous hospitality from the Hindu households. But, with the gradual progression of society, this discrimination is waning. We can name our children according to our wishes. There’s no restriction on that. We can name a child in any way we want. There’s no hard and fast rule that it should be a Hindu name or a Muslim name. For instance, my younger brother’s name is Sanuyar, which is a distinctively Muslim name. But my elder sister’s name is Swarna. No one would be able to guess if it’s a Hindu name or a Muslim name. Even my children have been named in this way. My son’s name is Hasheed Chitrakar. But my daughter’s names are Riya Chitrakar, Mou Chitrakar. So, we don’t have any problem giving Hindu names to our children.

Interviewer: Patuas have a lifestyle which departs in some form or the other from the path that has been ordained by the Islamic faith. So, now if the higher authorities start pressuring you into following a certain lifestyle, do you think that would hamper the communal harmony you nurture?

Manu Chitrakar: I have faith in an educated society; communal harmony would certainly be \emphasised more. If we can keep working in this manner and in this environment, a message on communal harmony would get propagated. Our community and our work are shining examples of that ideology. There was a time when eminent figures like Lalon Fakir, Rabindranath Tagore put in efforts so as to propagate the ideology of communal harmony. We, the patua community, are also trying our best to do the same. I am hopeful that such untoward incidents won’t happen in educated societies.

Interviewer: When a pata gets displayed in a fair or an exhibition…does the name of the village (Naya, Pingla) get emphasized or does the name of the individual artist get mentioned?

Manu Chitrakar: The name of the artist gets highlighted. The name of the village comes next.

Interviewer: The world acknowledges a pata as an artistic product from a certain village. The name of the village gets highlighted. Do you think that it is the name of the artist that should be brought into the limelight? Do you feel that the artist should be given his due recognition?

Manu Chitrakar: No, I feel it’s fine the way it is. Both the place and the artist are being mentioned now.

Interviewer: When patas on contemporary social issues are composed, there must be one patua who paints on that particular theme first and then the entire community takes up the same theme. So, in that case, does the patua get acknowledged individually? Or is it seen as a collective composition by the patuas of Naya?

Manu Chitrakar: Suppose I compose a pata song, and sing it during a fair. Some other patua might hear me and learn the song. He might revise it a bit and then claim it to be his original composition. There are several such instances. But that doesn’t create any problem. Our sole concern is about getting a patachitra acknowledged and appreciated. Obviously I’d like my name to be acknowledged as the original composer of the song. But that does not always happen. The other patua who has learnt would never admit that, since I have not taught him the song but he has picked it up while listening to me. Moreover, the song would also undergo some editing. He would change a few things according to his own taste.

Interviewer: There’s a pata on the tsunami. Could you kindly tell us who was the first patua to have composed on the theme? How did that pata come into being? Could you please narrate the entire story behind it?

Manu Chitrakar: The tsunami happened in the year 2004. We watched it on the television, on news, on radio, newspapers – everywhere. We composed the pata based on whatever we gathered from these sources. Several patuas have been composed on this theme. I have myself composed on the tsunami. Apart from that, my elder sister Swarna, Anwar, Babu Chitrakar and several others have also composed on this. Each of us composed it in our distinctive way. There was a gentleman from Delhi, called Rajeev Sethi. He has worked extensively on the tsunami. There was a programme going on there, in Delhi, at that point of time. So, there were patuas who composed patas on tsunami. When the topic garnered popularity, other patuas started painting on the same topic. They painted according to whatever they heard from the other patuas.

Interviewer: At that point of time, did the names of the individual artist get highlighted or was it the name of the village that got the limelight?

Manu Chitrakar: The name of the entire village got highlighted. It was propagated that the patuas from Naya are working on the tsunami.

Again for instance, I was the first patua to have composed a pata on the attack on the World Trade Centre. Some patuas were afraid to sing against terrorists. But then I was ready to take the risk. The incident had taken place in America, not in our country. Had it happened in our country, even I would have been apprehensive. I would have thought twice before beginning to compose on the topic. Since it was an incident from a foreign country, it was slightly easier for us to compose.

Interviewer: How did patachitra begin? Where did it originate? Is there any story behind it which you might have heard of or you know of?

Manu Chitrakar: We were told during our childhood that the origins of patachitra dates back to the era of kings, badshahs and nawaabs. It originated in a state in Bangladesh. A demon lived in the forests of that kingdom. It killed people, and devoured their flesh. The demon attacked every month. The king became very tense and started praying to the Almighty Responding to his pleas, the Almighty then sent a messenger – a Dervish. He asked the king what kept him so distressed. The king narrated the entire ordeal. The Dervish claimed that it can kill the demon. But the king laughed off the conclusion. Despite the efforts of so many subjects, he wasn’t able to keep the demon at bay. How could a mere individual be capable of such a mammoth feat? Dervish told the king that he was ready to go to the forest, fight the demon and kill it. Accordingly, he went to the forest and transformed a tree into a mirror. When the demon saw its reflection on the mirror, it attacked the ‘other’ demon. This is how the demon got killed. The Dervish came and informed the king that he was successful in killing the demon. The king, however, refused to believe it. That is when the Dervish took the bark of a tree and some leaves and started painting the entire incident. The king was grateful and wanted to reward him for his task. The Dervish requested to be granted the permission to paint and wander around villages, displaying his paintings. That is how patachitra and pata songs came into being. They were initially painted on barks of trees, using vegetable dyes. But it won’t be appreciated if the same old theme gets displayed over and over again. People want variety. Therefore, whenever a new incident took place, a patua started composing a pata on it. That is how patachitra began. Back then, patachitra was not confined to any particular sect. In Muslim households, patas on topics related to the Islamic religion were displayed. Likewise, in Hindu households, topics revolved around the Hindu religion. Gradually, patachitra became popular and it started being passed on from one generation to the other. This is the story we had heard when we were children. But I am not sure if this is true or not.

Interviewer: Do you still use vegetable dyes? Or do you use other kinds of colours as well?

Manu Chitrakar: No, even till this date, while painting patachitras, vegetable dyes are used. But keeping at par with the demands of the customer, we are also painting on T-shirts, saris and other forms of clothes. While painting on those, we use acrylic colours. Otherwise the colours would get washed away.

Interviewer: If you could please sing a pata song for us…

Manu Chitrakar: Right now I can sing a couple of lines. Singing the entire song would be a bit difficult.

Interviewer: That is absolutely fine.

Manu Chitrakar (to a family member): Could you please pass a small pata?

Manu Chitrakar: Would you please come over there?

Interviewer: Sure. Just a minute.

Manu Chitrakar:

Ramchandra got married. Following his father’s instructions, he left for the fourteen-year exile.

Ram was leading the path, followed by his wife Sita. His younger brother and the archer Lakshman followed them both.

The sun was scorching. The sand underneath their feet was also very warm.

Sita could no longer walk. She was almost melting away like a doll of wax.

Lakshman broke off a branch and held it over her head. He requested Sita to walk slowly under its shade.

They all arrived at the Panchavati forest. The brothers built a hut in that forest.

The hut was built by both Ram and Lakshman.

Ram and Sita used to while away their time playing, while Lakshman stood guard.

Surpanakha went to the forest in search of flowers. Her nose was cut off by Sita’s brother-in-law, Lakshman.

She ran back to her kingdom, Lanka, with her mutilated nose and started wailing at her brother Ravana’s feet.

Ravana was burning with rage. He immediately asked Marich (a conjurer) to leave for the Panchavati forest.

Marich took the form of a beautiful golden deer and allured Sita. The moon-faced Sita, while playing dice, looked at the deer and requested Raghuvar to bring it to her.

Ram immediately started chasing the deer.

Marich ran away. He emulated the voice of Ram and cried out for help.

Hearing Ram’s plea for help, Sita called Lakshman for help. She gave him a betel nut and asked him to immediately rush to the forest and rescue his brother.

Lakshman drew a boundary line and asked Sita not to venture beyond the threshold.

Then, Ravana emerged from behind a banyan tree.

The moment Sita crossed the threshold to give away alms to Ravana (dressed as a beggar), the latter abducted her and brought her to Lanka.

Ram asked Jatayu to tell him where Sita was and what had happened to her.

Jatayu narrated whatever he had witnessed.

He had been fatally injured. He fell at Ram’s feet and chanting Ram’s name, breathed his last.

Here my pata song on the Ramayana comes to an end.

My name is Manu Chitrakar and Naya is my address.