Transcript

Interviewer: Okay… so first we would like to know your name.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: My name? Dukhushyam Chitrakar. Address? My father’s name is Amulya Chitrakar. My guru’s name is Gunadhar Chitrakar. I was born in (I’m saying this in Bengali) Kolkata’s Sambhunath Pandit Hospital. My father used to make earthen idols while my mother stayed there. My native place is Sutahatapur, Purba Medinipur. I was brought up at my maternal uncle’s place. I lost my father when I was just a month old. After that, we had to endure abject poverty. I have created my autobiographical pata. I created patas depicting the origin of the community of patuas, and that too at a very young age. I have studied only till the first standard. Yet, I have composed songs, which no graduate has been able to outperform. This is a talent! Let me give some examples. The Hindu god Vishwakarma, ceaselessly keeps doing his job in this world. Why? Because he is the eighth son. In our Muslim tradition, Dervish is the eighth son. Sri Krishna is also the eighth son. They all are highly talented. Rabindranath Tagore was also the eighth son. He was also extremely talented. Dukhushyam Chitrakar is also the eighth son, is highly talented and even till this date, not a single patua has been able to surpass him. (I have narrated this in Bengali. Now it is up to you, how you would translate and explain it to the concerned person).

Interviewer: It is only in the last week that I came to know of the existence of an entire village near Kharagpur which paints. I was not aware of this.

(You did not know that a patua village existed).

So if you could please explain the kind of work that is done here, in this village.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: : The patua community is as old as man himself. This is not a community that has appeared recently. The origins of the patua community cannot be located It is that old! As no one can pinpoint the exact date of origins of the human species, similarly, the origins of this community, too, can never be traced. Be it the Muslim patuas, the Hindu patuas, or the Santhal patuas, the origins cannot be located. It is an ancient community. We are born and brought up amidst nature – trees, flowers, fruits and the earth. We use the same things to portray our art as well.

(Are you able to follow my words?)

So, as I’ve already mentioned, the patua community is ancient. I have also made patachitras depicting the birth of patuas, my autobiography, as well as the biography of Rabindranath Tagore.

Interviewer: How long have you been living here?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: At least sixty years. There was no one here, initially. People migrated from Purba Medinipur to this place and settled down here. At the beginning, there were just three families. People started coming and settling here, much later. The first-wave migrants would be around sixty- to sixty-five years old now. This has now become a village of the patuas– a small settlement of their own. No patua village existed here before this.

Interviewer: Are all the inhabitants of this place painters?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Yes. Everyone paints. But not everyone knows the songs.

Interviewer: So who are the ones who know these songs?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: The ones who have learnt the songs can sing. How would the untrained ones sing? Anyone can paint. But then they’ll not be able to sing. Neither will they be able to give an explanation of the subject of the paintings. They won’t be able to explain even their own paintings. One can imitate the motifs, but how will he explain it? Until and unless one learns the meanings oneself, how will he tell others?

Question: What are the usual themes of your paintings?

Answer: The themes are usually mythological. They are based on the Mahabharata, the Ramayana, the Mangal Kavya. Again, drawing from the Muslim corpus, we have the pir tradition. We have fairy tales. We also have contemporary social issues, many environmental issues, issues like natural disasters. Patas comprise a wide range of themes. The local flavour gets mixed into these patas. Songs are composed using the local traditions. Earlier, the elderly patuas used to summarise the essence of the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, and used them to advertise something. Patachitras. earlier, were a form of advertisement. You watch advertisements everywhere, don’t you? Earlier, there were no televisions, no radios, no films. The patuas would wander about villages and counsel people. They would give right advice.

Do you understand Bengali? I keep interjecting my statements with witty lines. For instance, you people study and then try to grasp meanings . There’s no point if you can’t comprehend the meaning. Nowadays, they are producing all these romantic films. Srimati Mamata Banerjee (the honourable Chief Minister) is the only one protesting against all these. Why? Don’t you have anything else to showcase? Are you teaching the common masses or trying to misguide them? Has this become some sort of a joke now? Adultery is being shown. What about morality? What is this? They are making such trash films these days that the state government has to intervene and reprimand them. The makers of these films are all educated. But what are they doing with all their education?

Patuas, earlier, were considered as a reservoir of wisdom. They used to impart knowledge to the common masses. For instance, a widow in medieval India was burnt along with her husband on the same pyre. Eminent men like Vidyasagar protested against this practice. Didn’t they? Likewise, patuas also imparted the right knowledge, gave the right advice to common people. Patuas depicted stories of Savitri who brought her husband back from the clutches of Yamraj (the king of the dead). Lakhindar (from the Manasa Mangal) passed away. But his wife, Behula, sailed for six months at a stretch and brought back her dead husband. They had put their faith in the Almighty. They were all chaste. These were the stories, the repositories of knowledge that were unfurled by the patuas. Patuas were highly respectful of their gurus. They, therefore, sang songs which had nuggets of wisdom in them. They guided human beings from darkness towards light. When you hear the stories for the first time, you learn something new. Therefore, you move a step forward, towards light. This is how patuas have maintained this tradition for several generations. It is similar to how a baul or a fakir community works. So, that is how mass consciousness is awakened.

Interviewer: Did you all migrate from Purba Medinipur?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Yes. We all came from Purba Medinipur. At that time, Medinipur was undivided; the concept of Purba (east) or Paschim (west) Medinipur did not exist.

Interviewer: Yes. Earlier there was just one Medinipur. It was one of the largest districts of India.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Yes, yes. That’s true. Like earlier, during the British regime, there was one undivided India. It wasn’t partitioned into Hindustan, Pakistan. The British, before leaving our country, engineered this. Likewise, Medinipur was divided much later. Look at all the states being divided now. It has been prevalent since the time the British left.

Interviewer: You were saying that patuas usually compose on mythological themes. Do you also compose on contemporary issues?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Of course.

Interviewer: What are the kinds of contemporary issues that you usually choose to deal with in your patas?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Issues like afforestation, cleanliness.

Interviewer: Yeah…Issues that have been taken up by the Modi government.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: It has got nothing to do with the Modi government. Cleanliness is something that should always be practised no matter what. Why is the name of Mr. Modi being dragged into this? Now, when he suddenly announces demonetisation, certain currency notes get banned. Why? Obviously because he is in power. Once he steps down from that position, his words would cease to be this powerful. It is not about Mr. Modi at all. The fact is that if man wants to improve, he himself has to become aware about these issues. Until and unless man himself becomes aware of them, nothing is going to improve. It doesn’t matter if Mr. Modi or Ms. Mamata Banerjee coax you a thousand times. Man himself has to become conscious. For instance, if cops think of chasing thieves, they must make sure that they themselves are on the right path. Otherwise, they cannot slam charges against people they themselves are guilty of. These are all instances.

For example, policies like Kanyashree, Sikshashree, Nirmalshree – these are all contemporary issues. Just like the tsunami – a natural calamity, lives of revolutionaries like the death of the martyr Khudiram Basu, Subhashchandra Bose – contemporary burning social issues are taken up by patuas. A patua even lost his life for having composed the Sahebpata. If I compose songs about the Sarada scam, I’ll immediately be shot. So, the people around have been warning me not to take up such issues.

Interviewer: Has the number of chitrakars remained the same, since the time they settled down here?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: The number has, in fact, increased. Earlier, the number was very less; there were just three patuas. It was like the Holy Trinity – Brahma, Bishnu, Maheshwar. There were just three families. From there, it has now increased manifold. Now it has multiplied thirty times.

Interviewer: Is the quality of work being produced in contemporary times at par with the ones produced earlier?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Will pure gold ever be worthless? No. Right? But if you adulterate it? Then, what? The quality of adulterated stuff is higher these days. Pure gold remains neglected because of its high price. If people get adulterated gold at lower prices, why would they even care to buy the real thing?

People are all bothered about money. They would rather buy adulterated things at lower prices than buy genuine things at a higher price. But then a connoisseur, a true appreciator would always be drawn towards the genuine product.

Interviewer: Yes, the one who realises the worth of the product.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Absolutely correct. This has always been the standard practice. The only difference is that, perhaps, it is practiced more these days.

People were less educated back then. But they held on to some core values, morals and ethics. But nowadays, people are more educated. But there is a dearth of basic morals and principles. Very few people can be called wise.

We regularly hear of incidents where professors are physically assaulted by their students, where fathers get beaten up by their sons. Earlier we had the practice of younger people touching the feet of the elderly as a mark of respect. But everything has become so westernized these days. We even address our parents in a manner similar to the West. This is where our values, our education, has brought us to.

For instance, I have about a hundred songs in my repertoire. Manimala knows around ten to twelve, or perhaps fifteen. How would she know more, until and unless she comes and learns them? For learning these songs, she needs to invest her time. Where would she get that time?

Interviewer: So, basically what you are trying to say is that people want to learn more, without actually investing the right amount of time.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: In fact, these days people don’t even want to learn.

Interviewer: Right. True knowledge is not pursued anymore. All they are chasing is degrees.

What is the medium on which these paintings are made?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: We paint on all kinds of media. Earlier, we had handmade paper. We also paint on earthen items – those are called pata. We also composed on the walls of temples. Nowadays, even ashtrays are painted on.

Interviewer: What did the patuas do before settling down here?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Listen to the history of the patuas now. The patuas would wander about villages. Within a span of twelve months, they would have moved between twelve different places. They were nomads. In order to earn their living, they had to leave their houses for different places. Women and children would stay back. Only the husbands would leave for work. Earlier women did not sing or paint. But yes, they made dolls that were sold in fairs. So, these men visited various places, sang songs and displayed their patachitra. Patuas were so good that they were trusted by all. If they wanted to stay in someone’s place, they were never turned away. They were warmly welcomed. Like this, they used to visit places at different times of the year. For instance, during the Durga Puja, patuas used to visit Chandrakona (not the road, but the town).

At that time, people used to present innumerous saris to the patuas. Earlier, people used to present brass and copper utensils as well. They did this out of love. On being pleased with the works of the patuas, people would reward them with gifts. Patuas would never buy their own clothes. They received clothes as rewards from people. They did not even have to buy their own utensils. They were given utensils of brass. Many people also wanted to give them lands for farming. But how can someone, who roams about different places all throughout the year, engage in farming? So, they did not accept land as rewards. But, now, people have become smarter. The prices of land has also gone up. So, now they have realised the importance of acquiring these things. It would be convenient to own land. But now no one would give away land that easily. In fact, the three patuas who were amongst the first settlers here had received land as a reward. They were even provided with the basics – like bamboo, and straw for building their huts.

Interviewer: Now they won’t give away land this easily. The prices have increased by leaps and bounds.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: (laughing) Who would give land now? They wouldn’t even give steel utensils any longer.

This is how the scenario was. The patuas would wander about villages from door to door. They would meet their expenses with those earnings. Now patuas do not visit villages anymore. They all flock to cities. They are visiting countries like America, Russia, Japan and Germany. It has become a completely urban enterprise. Urban practices have percolated the rural fabric and vice versa. This is where the difference lies.

Interviewer: But that is a good thing.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Yes. There’s no doubt that it is a good thing.

Interviewer: At least people would become aware of these practices.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: That is true. But in order to propagate it, you need an able person. That able leader is missing now. You need to continue the legacy of your forefathers. For instance, Mr. Sudhanshu Roy was one such person. David McCarthy, an American – he, too, was one such eminent figure. These people ensured that core practices and beliefs were maintained. You might be educated. You might be rich. But you are chasing the glitter, not the gold.

Interviewer: You were mentioning a few minutes back that patuas visit foreign countries for showcasing their talent. Do you think the patuas do not get ample opportunities in their own country?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Yes. These works are more appreciated in foreign countries. But then the fact remains that the genuine patuas, the ones who have truly embraced the essence of this art – they still remain unacknowledged. They are not the ones who are being given opportunities abroad.

Interviewer: What exactly do you mean by the term genuine?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: There are ingenuous patuas amongst us as well. As I have already mentioned, there might be patuas who can paint, but cannot compose songs. They hardly know two to three songs, but they are the acclaimed ones.

Let me give you an instance. There was a girl from IIT Kharagpur. She came here looking for a job in a high school. Despite having a good profile, she was asked for a bribe amounting to one lakh rupees. She refused to pay a single penny. She said that she was qualified enough for a job where she won’t have to bribe someone to get through. After a few months, a far less qualified candidate paid a hefty sum and got the job. The girl who had refused the job is now a professor in the Medinipur College. She knew she had substance; she had knowledge. She knew what her capabilities were.

Now, the ones who are inviting the patuas to foreign lands are all foreigners to our language and culture. How would they comprehend the essence of this tradition? They need to be informed. But the patuas who should bear the responsibility of informing them are themselves ignorant.

Interviewer: Right. The patua himself needs to be aware of the traditions.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Suppose you like a pata and you want to buy that. But there’s no point in just buying a pata. What about the music that is supposed to accompany the pata? Only when the music is played alongside does the pata come alive. This is where the difference lies between a pata and a painting from an art college. There’s life in a pata. Pata is the predecessor to films.

Have you ever seen the mythological figure of Rama? No. But when a patua paints him, and sings along, you start visualising him as Ram. All the other characters like Sita, Lakshman, Ravana, Hanuman come to life in a similar fashion. It’s just like a puppet show.

Pata is not just about buying the image. It is equally about the song. The song enriches the quality of the pata.

Interviewer: Do you think the next generation will be able to carry forward this legacy?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: I don’t think so. You know why they won’t be able to hold on to this? The media plays a huge role. They would focus on particular patuas. They would bring them into the limelight. But what about the other patuas? How would they survive? They have to take up some other profession for their living. So when would they compose the pata? If I become a tea-stall vendor, would I have enough time to devote to pata? A cowherd can compose songs, but a district magistrate cannot. He is shackled to the constraints of time. A boatman, too, has time for these things. He is not a slave to a mundane routine. He is a free soul. Have you heard bhawaiya songs? The notes are high-pitched. You know why? The boatman’s pitch has to soar high – high above the sound of the waves. What are the urban folks doing with these songs? They are trying to exert their influence on these. But they are unable to appreciate the essence of these folk compositions.

Interviewer: You all are being invited to foreign countries for delivering lectures at several workshops and seminars. Why aren’t such things being done in India?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: That’s not true. Even in India such workshops and seminars are hosted.

Interviewer: Yes, I agree. But then, the number of such workshops being held in India is pretty less in comparison to those conducted abroad.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: I’ll give you an example. Anjali Madam likes Manimala. She also likes me. Therefore, she has given us a platform for us to showcase our talent. Similarly, someone else from some other university might arrive and provide a few more patuas with such opportunities. One has to be aware of the existence of the patua community and their practices. Only then can they disseminate their knowledge to others. So, the educated class has to be instilled with an awareness, an appreciation for these things. If the work of art is not brought into the limelight, how will it survive?

Interviewer: Based on what criterion do the people from foreign countries select you?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Obviously based on the pata and the reputation of the patuas.

I’ll show you all my patas, sing the songs, but only after the interview is over.

34:23- 36:10 – routine conversation

Interviewer: What is the typical size of your patas?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: It varies according to the medium.

Interviewer: Okay. That means that your work on paper is bound to be different from that on a pata.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Even when patachitra is made on paper, the size is not fixed. It can be on a small sheet of paper or on a long scroll. There is no standard size as such. I’ll show you some of my patas.

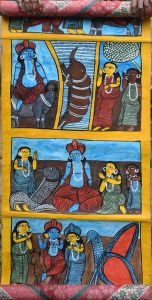

This is a pata on the Hindu lord Vishnu. Note the size of the pata. Then again, you can also have a pata like this – the images of Radha Krishna, painted on a narrow sheet of paper. Patas are made on standard A4 sized sheets as well.

This is the pata of a Santhal. We also have patas on Hindu goddesses like Lakshmi, Saraswati. Patas on Muslim pirs are also composed.

This one is on Radha Krishna.

Interviewer: How long does it take to compose one pata?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: At least three days. You have to wait until the dye dries.

Now, these patas do not have songs accompanying them.

Let me show you the patas which have songs. These are the Babu patas.

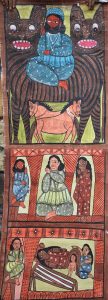

These are the Muslim patas– Bonbibi?.

Interviewer: So you have songs accompanying these patas?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Yes.

Interviewer: What are the stories behind these patas?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: The stories are all narrated through the songs. For example, this is the story of the Hindu god, Ganesha. Then you have episodes like Dakshayagna.

Interviewer: Is there any difference in the styles that were used earlier and the styles that are used now.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: No, no.

Interviewer: So, you are still continuing with the age-old tradition.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: As I mentioned earlier, true artists would always cling to tradition. For instance, Kalighat patachitra is a form of Bengal art. Our patachitras, too, are forms of Bengal art. They represent the quintessential Bengali way of life. They will always remain the same.

Interviewer: What does this patachitra depict?

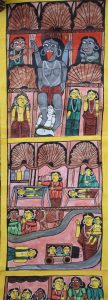

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: This is a scene from Chandi Mangal. Look, this is the Asura. This is the lion. These patachitras have songs. The entire story is narrated through the songs.

Interviewer: How long have you been doing this?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: I have been doing this since my childhood. I even went to jail once (for an hour) for my songs. It was regarding a rebellion. I learnt these songs when I was just eight years old. I used to go to school and then come back and learn the songs from my maternal uncle. Since my father had passed away, I used to visit villages singing these songs.

Interviewer: How old are you?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: I am seventy-five.

Interviewer: So it has been more than sixty years that you have been doing this.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Yes.

Interviewer: I have heard that earlier all the patuas would flock together, and sing the songs in a chorus.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Yes. It is still prevalent. But then the individual patuas have specific people singing for them. For instance, when we are invited for programmes, we have to select individual singers. We cannot include everyone. We may select three girls and two boys…people who regularly practice singing. This practice of singing in a chorus is only seen when there is a cultural programme. The art of composing songs, singing them alongside the patas – this entire practice has declined. These patuas visit other places, other countries only with the target of selling some patachitras. They are forgetting the songs. But this is not what I want. You might get customers for your patas. But what about the songs? People need to be made aware of the songs. This is where my opinion differs from other patuas.

Interviewer: Right. Otherwise the story behind the patachitra will eventually get lost.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Knowing the story behind this is extremely important. Why are patachitras considered so valuable? You need to understand the story so as to be able to comprehend its worth. Patachitras are valuable because they have a narrative.

Interviewer: So…you have preserved all your patachitras.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Yes. I need to paste a piece of cloth behind these patas, so that they become durable. I have made quite a number of scrolls. But I’ll show you the smaller ones.

Where have you kept the patas?

Background: Which one?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: The small patas.

Background: I have kept them on the shelf.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Wait, I’ll show you. I have several long scrolls.

Background: Yes, there are several long scrolls.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: I’ll be showing only the small ones.

46:04 – 46:25 Routine conversation.

Look … this is the Chandi Mangal pata.

Interviewer: So this patachitra has a story.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Yes, and a song too.

46:44 – 47:21 (has to be edited)

This is also a patachitra based on the Chandi Mangal. This is depicted on a smaller scroll so that it can be kept as a wall hanging.

Interviewer: What is this pata depicting?

Dukhushyam: This is based on the Chandi Mangal. This can be used as a wall hanging. The size is pretty handy.

Interviewer: It would be nice if this painting could be held in a frame.

Dukhushyam: In that case, it would survive for a thousand years more.

Interviewer: If you could kindly sing a song…

Dukhushyam: Of course, I’ll sing. Do not worry. But let me showcase these paintings first.

This is on the marriage of fishes.

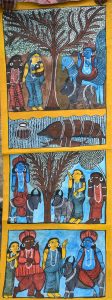

This one is a Santhal (tribal) pata. This looks good, doesn’t it?

Interviewer: Yes.

Well… which form of dance is this?

Dukhushyam: This is the Santhal (tribal) dance. They are intoxicated and are engaged in singing and dancing.

Interviewer: There’s a dance form called Chhau, which is practiced in Purulia. Right?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Chhau and Santhal are two different forms of dance. There are several forms of dance.

These patas fetch more customers. People prefer patas on such themes. Interviewer: Have you used acrylic paints for this pata?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: No, no. These are all vegetable dyes. We mix the resin of the Bengal quince. It makes colours look brighter.

Interviewer: How do you prepare these dyes? For example, how do you get the yellow colour?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: From turmeric. We get the green colour by mixing a paste of buffalo spinach and Indian beans. The blue colour is obtained from butterfly pea flowers.

IIT Kharagpur had helped us by giving a few plants from which we could prepare such vegetable dyes. The yellow colour here has been mixed with catechu. So, basically we prepare our colours by mixing a lot of things. But these are all natural colours.

Interviewer: What about the green colour?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Buffalo spinach and Indian beans.

This pata is also based on the Chandi Mangal.

Interviewer: What is this pata depicting?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: This is also on the Chandi Mangal. This has a song as well. The story is the same as the one you saw earlier. The styles are different. Let me sing a song. I’ll sing the other songs later. Is that okay?

Interviewer: Sure.

All hail our mother, goddess Durga, She is the destroyer of all woes.

In the southern part of India, she is also known as Nagendra Nandini.

She has ten hands, adorning ten different directions.

Her third eye burns right in the middle of her forehead.

Goddess Durga has her children – goddess Lakshmi, goddess Saraswati, lord Kartika and lord Ganesha by her side.

Having defeated Asura, the lion, too, walks beside the triumphant mother.

One fine morning, goddess Durga felt compassionate and came down to meet Kalketu under the shade of the pomegranate tree, in the guise of a chameleon.

Kalketu, ignorant of the goddess’s guise, caught hold of the chameleon and put it inside an earthen vessel. He brought ‘it’ home.

His wife, Phullara removed the lid of the vessel and watched the chameleon transform into a beautiful woman sitting at the threshold of the hut.

The ascetic man (Dhanapati) was imprisoned for twelve years.

Meanwhile, his wife Khullana, gave birth to a child named Srimanta.

Srimanta was a profoundly learned and wise man.

He expressed his wish to embark on a quest to find out his missing father.

Khullana became perturbed on hearing this. She said she could let her only child embark on such an arduous journey if goddess Durga could be summoned to accompany him.

Responding to her prayers, goddess Durga descended.

Khullana handed over the responsibility of her son to goddess Durga.

Srimanta boarded the ship while singing praises of goddess Bhavani (Durga).

Even when lightning struck, and the weather was turbulent, even when a congregation of alligators swarmed around,

Goddess Durga sat still on a lotus, along with her son Ganesha.

Kamala Kamini (Durga) was seated amidst a hundred lotuses.

It seems as if Ganesha’s mother is devouring a hundred elephants.

The ship kept sailing.

The king of Sinhala was seated on a bejeweled throne.

On a bejeweled throne, king Shaliban (?) was seated.

Srimanta stood in front of him with folded hands.

Srimanta narrated how he had witnessed Kamala Kamini braving all odds and devouring elephants, despite being a woman.

Hearing his story, the king said that he would give away half his kingdom and his daughter’s hand in marriage, if Srimanta could prove what he narrated.

The king further added that if Srimanta couldn’t prove his words, he would be killed

The king of Sinhala made up his mind and left for Kalidaha to get a glimpse of Kamala Kamini.

The goddess of wisdom, mother Bhagwati (Durga) hatched a plan.

She hid herself amidst a cluster of lotuses.

Srimanta failed to prove his words and was in an awkward situation.

The king called for the security personnel and got him arrested.

Goddess Durga appeared in the guise of an old Brahmin lady.

Immediately, Srimanta’s shackles got unfastened on its own.

The king had ordered his guards to behead Srimanta.

But goddess Durga stood in front of them with her eighteen hands.

The houses graced with your presence, oh mother, and the people who have worshipped you are indeed blessed.

Even Indra became the king of gods because he worshipped you and had your blessings.

I give you a boon, Srimanta. I give you a boon.

Get married to king Shaliban’s daughter.

Srimanta got married to the king’s daughter.

People from all corners of the country were welcomed to the grand wedding feast.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Each pata has a different story and a different song.

Interviewer: Have you written the lyrics of the song by yourself?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: No. These songs have been handed down by our forefathers. All these songs on the Mangal Kavya, the Ramayana have been composed by senior patuas.

Interviewer: Don’t you write new songs?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Yes, I do.

Interviewer: What about the tunes?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: The tunes are also mine. I write my own songs and also decide the tune.

Interviewer: You don’t have any musical instrument (like a tabla) accompanying these songs. Right?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Yes, sometimes such instruments are played alongside, but then it’s not possible for an individual to do everything all alone. It is used only when a group has to perform somewhere.

Interviewer: Okay.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Earlier, people used to perform in groups. They shared cordial relationships. But those are missing now. Haven’t you witnessed feuds between siblings?

Interviewer: True.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: That is exactly what I am trying to say. I’ll sing a few other songs, then.

Interviewer: Okay.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Do you have any other questions?

Interviewer: Let me ask him. Do we have any other questions?

55:45 – 5:55 – routine conversation.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Okay, I’ll show you the other patas, then.

55:58 – 57:01 (has to be edited)

Interviewer: This scroll is pretty long.

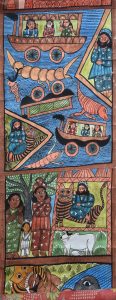

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: We have scrolls that are longer than this. Patas used to be long because of the song that accompanied it.

Interviewer: You require people to assist you with these long patas, isn’t it?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Yes, one person sings and another person holds the other end of the scroll.

Interviewer: You must be requiring at least two people? Is it enough to have just a single person accompanying you?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Yes, yes. One is enough.

There are so many varieties of patas. You need to understand that.

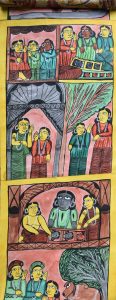

This is on the origin of patachitra

This is on Krishna Leela. This, too, has a song accompanying it.

You must have heard Runa Laila. She has borrowed this tune.

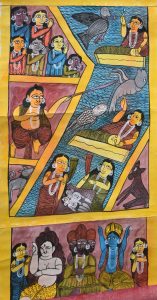

This is on the Ramayana. This panel depicts the episode of the golden deer and this one is the abduction of Sita. This is Jatayu.

We have a huge variety of patas. Do you want to have a look at this old pata?

Interviewer: How old is this pata?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: First, have a look. If you get this in a frame, it would become very convenient to display in one’s house.

Some people had come down from the Rabindra Bharati University to collect and curate these.

1:00:14 – 1:00:45 – routine conversation

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: This is on Manasa Mangal. This revolves around the story of Behula and Lakhinder.

1:01:07 – 1:01:35 – routine conversationDukhushyam Chitrakar: This one is on the Santhals. The lyrics of the pata songs is also in Santhali language. Do you want me to sing it?

Interviewer: Sure.

1:01:56 – 1:02:12 – routine conversation

Interviewer: Have you made all these patas?

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: No, they are not just mine. There are several other people who have painted them. But I have preserved them.

This pata is about the marriage of fishes. This, too, has a song. This is a small pata, but we have longer scrolls on the same theme. The tune is different here.

Hey everyone let’s go…let’s get the young fishes married.

Let’s get the trouts married.

Let’s get the carps married.

Let’s get the young fishes married.

At first, the swamp barb says that we’ll all leave together for the wedding (2)

We can dance for the wedding even in shallow waters.

Let’s go…

Let’s get the young fishes married.

Tyangra fish says that they, indeed, need to leave for the wedding (2)

The swamp barb would dance and swim, and also play the harmonium.

Hey everyone…let’s go.

Let’s get the trouts married.

Let’s get the carps married.

Let’s get the young fishes married.

Walking catfish and the stinging catfish decide amongst themselves that one will become a boat, and the other will become a dinghy (2)

The Bengal Barb says that it wants to sing the wedding song.

Let’s get the trouts married.

Let’s get the carps married.

Let’s get the young fishes married.

The Wallago and the Barramundi also arrive.

The evil Snakehead Murrel also joins them. They are all furious and they decide to gobble up all the other fishes.

Let’s get the trouts married.

Let’s get the carps married.

Let’s get the young fishes married.

Dukhushyam Chitrakar: Okay. I need to cite a few examples in order to explain this. Wait…

Oh those breasts of yours…they are my earthen pitchers.

That long black hair of yours is my rope.

Oh the ripples of your love…that is where my Yamuna is.

My deepest desire is to immerse myself completely in that body of yours.

Hearing those lines, Krishna turned its flute into a black snake.

The snake hindered Radha’s way.

It coiled around her left foot and bit the right one.

Radha could barely walk. She collapsed after a few steps.

She started calling out Krishna for help.

“Where are you, Krishna? Please give me a glimpse,” said Radha.

Please allow me one glimpse and save my life.

Krishna replied, “I am the guardian of the orphan. I am the Lord of the helpless.

I can be a venomous snake and bite people. Again, I can be a snake charmer and heal one’s snake bites.

I am the Lord of the helpless.

Lord Krishna comes to Radha’s aid and asks her to tell him honestly how severe has been the poisonous pang.

The poison gets removed and Radhika regains consciousness.

Hearing Krishna’s words, Radha finally finds herself all alone (?)

She sees her husband, Ayaan Ghosh standing in front of her.

She wonders…the dark bud (Krishnakali) has finally become one with Banamali (one who wears garlands made from wild flowers).

But to preserve the sanctity of Radha’s marriage to Ayaan Ghosh, and to keep her away from Krishna, her mother-in-law Jatila and her sister-in-law Kutila start hatching plans.