Transcript

How long has the patua community been living here?

Yakub Chitrakar: The Patua community has been here for almost –

Let me tell you about myself.

I have been living here, in Naya, for almost forty years.

Patuas have been living here for the last hundred years.

Before this, I used to live in a place which was under the

jurisdiction of the police station of Nandigram, Purba Medinipur.

Now it belongs to the Chandipur police station.

The name of the village is Hobichak.

I migrated from that place to this village and it has been forty years since I have settled down here.

Interviewer (TM): Were you the first person in your family to have moved to this place

or did any of your predecessors come here before you did?

Yakub Chitrakar: No, my brother first came to this place, along with other elderly members.

We came later.

Interviewer (TM): Okay.

So you are not the first member in your family to have come and settled here.

There were others who came first.

Yakub Chitrakar: My brother and I came here almost at the same time.

But there were other patua families which had come and settled down way earlier.

But, yes, I have been here for the last forty years.

Interviewer (TM): From whom did you learn patachitra?

Yakub Chitrakar:This is something that has been handed down by our predecessors.

I have learnt it from my father.

I have taught this to my children and also to my son-in-law.

Interviewer (TM): Back at Nandigram, did you work as a patua? Or were you involved with some other work?

Did you start practicing patachitra only after you settled down here?

Yakub Chitrakar: We practiced patachitra even when we were in Hobichak but then we weren’t this dependent.

Now we have become a lot more dependent on patachitra as this has become our sole means of earning.

But in those times, the market value of patachitra was not that high. Patachitras weren’t sold.

Patuas used to wander about villages with their patas singing pata songs.

We had to subsist on whatever (money, a handful of rice, some vegetables) the villagers gave us.

But there were times when I had to take up several other jobs.

Let me tell you about my own experience.

I was associated with patachitra.

But then, for survival I had to do other things like quarrying, grazing cattle.

I have worked as an unskilled labourer and have been into the weaving industry as well.

But why have I done these?. That was a period of abject poverty

and struggle and patachitra could never be our sole means of livelihood.

I was into so many other jobs before finally switching over to this.

While living in Nandigram, I used to work intermittently on patachitras.

That was the time when the market value of this art form was gradually improving.

But after we moved to this place, everything improved significantly – the paintings, the songs, and their demand.

Interviewer (TM): How old were you when you came and settled down here in Naya?

Yakub Chitrakar: How old was I… well, around fifteen or sixteen years old.

Interviewer (TM): Was the number of patua families back then, the same as the number of patua families that are there now?

Yakub Chitrakar: No.

There weren’t so many patua families back in those days.

Now you’ll find around eighty families here, who are associated with this.

Earlier, there were approximately seven, eight, or perhaps, ten families.

Interviewer (TM): So, the number has increased considerably.

Were your contemporaries and the ones who came and settled down much later,

too, involved in some other work like you?

Did they make a comeback only after shifting to this place?

Yakub Chitrakar: Yes, a similar thing happened with all the patuas here.

We have had to explore many other options and had to struggle a lot.

Despite everything, we clung to our age-old tradition.

Interviewer (TM): What is the typical theme of your patas?

Yakub Chitrakar: Well, if you ask me about themes, then let me tell you another thing.

That would make it easier to explain.

A thousand years back… perhaps two thousand years back, how did they paint?

They painted on the barks of trees using vegetable dyes.

They didn’t have separate paintbrushes.

They used to dip their fingers in colours and paint.

Much later, they started making paint brushes out of the fur sheared from the nape of a goat.

They did everything on a bark.

Then, they wandered about villages displaying these barks and singing along with that.

Later, what they started doing was resizing the barks into small, square pieces like the square patas these days.

Obviously, the barks were not of uniform shape and size.

So, their shapes had to be adjusted accordingly.

They carried these square shaped barks and continued singing and displaying, the way they did.

With time, the medium kept changing.

Instead of barks, they started painting on pieces of cloth, art paper.

We now paint on art paper, on canvas, on garments like saris, shirts, t-shirts, etc.

The colour we use for these are, however, different.

We need to use fabric colours.

We cannot use vegetable dyes for clothing.

Otherwise, the colours would get washed away.

Interviewer (TM): So, basically you are adapting patachitra according to the demands of the market.

Yakub Chitrakar: Exactly.

The fifteen-twenty feet scrolls that we usually display at Kolkata are the ones that we used to showcase at different fairs.

People used to come and compliment us on our patas.

They would appreciate how beautiful the Manasa Mangal pata was.

But, at the same time, they would also add that they could have taken it back home, had it been on a shorter scroll.

Some others enquired if the patachitras could be narrated on garments as well.

That is how we started changing.

We started making smaller patas –

We adjusted the size so as to be able to fit modern households.

depicting mythological stories and other social contemporary issues.

We became aware of the needs of the customers and started painting on myriad things – cups, saucers, glasses.

We have also started earning well because of this change.

Interviewer (TM): Do you still paint on mythological themes?

Yakub Chitrakar: Yes.

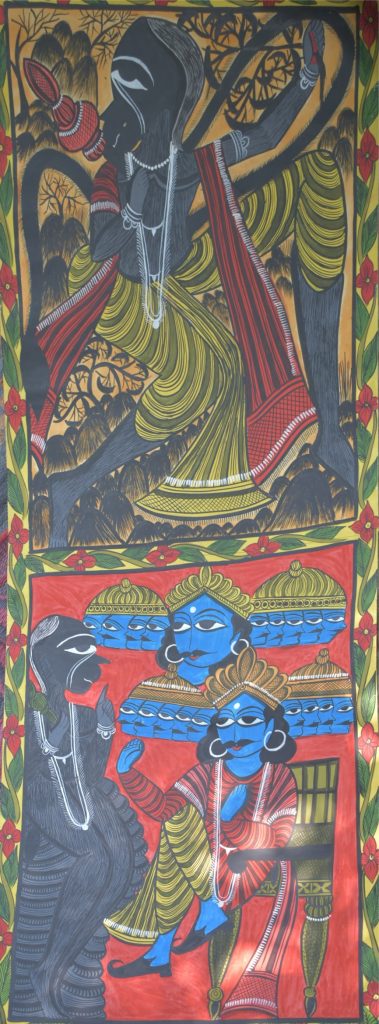

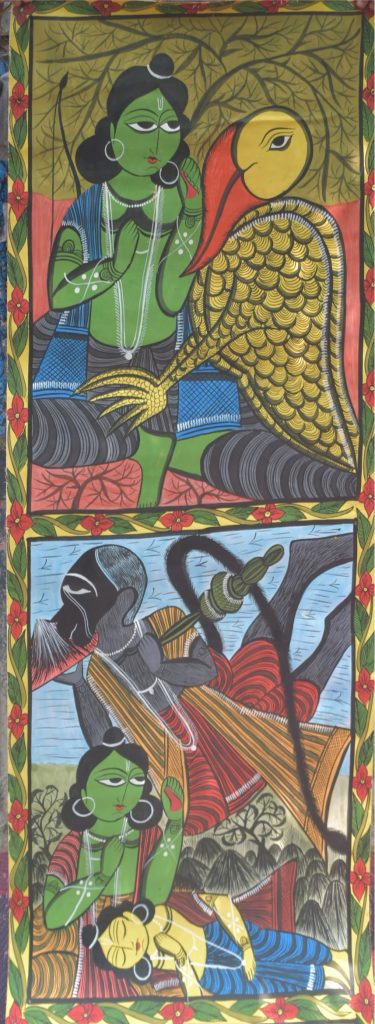

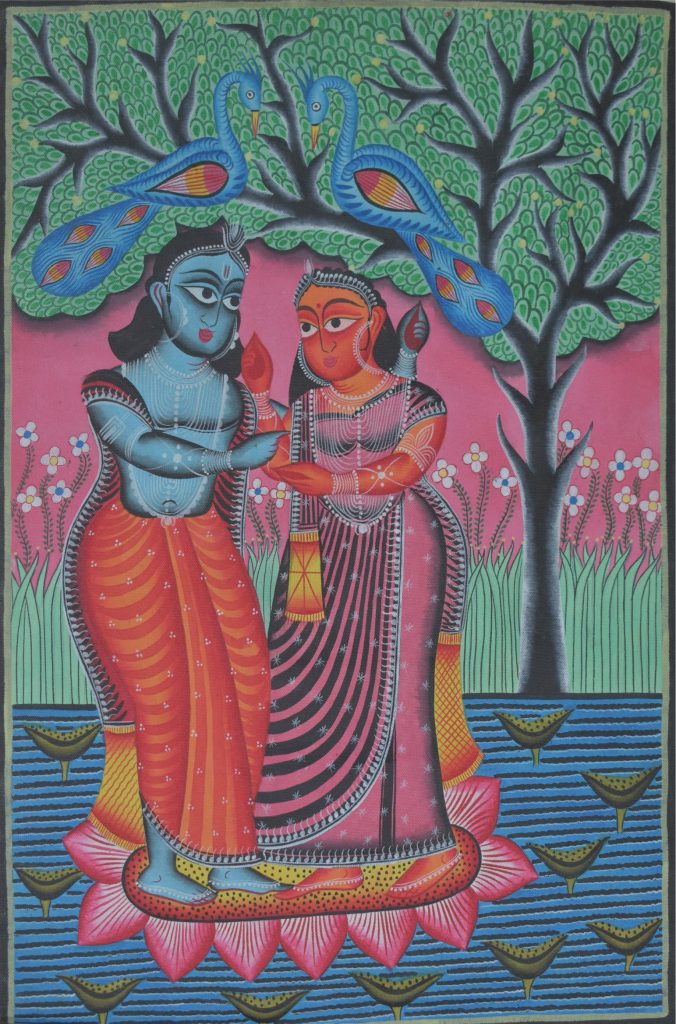

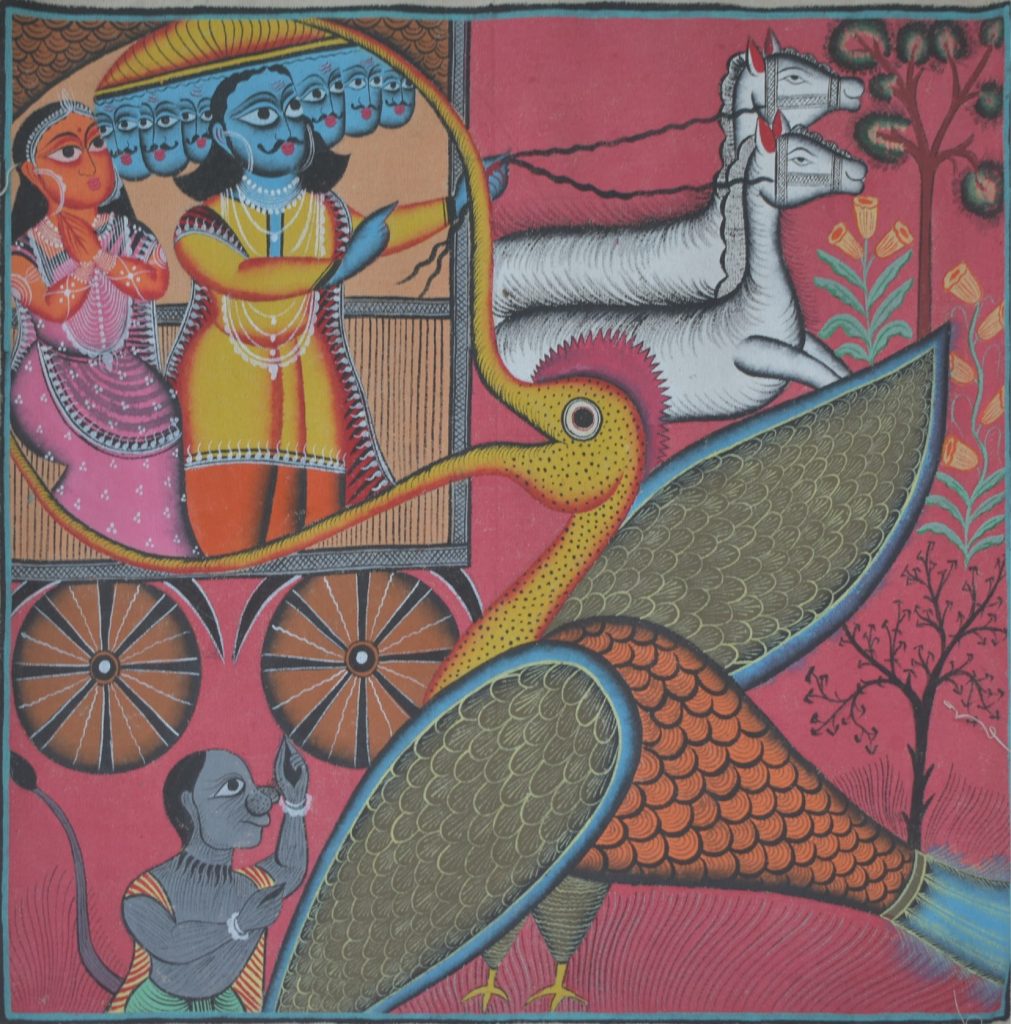

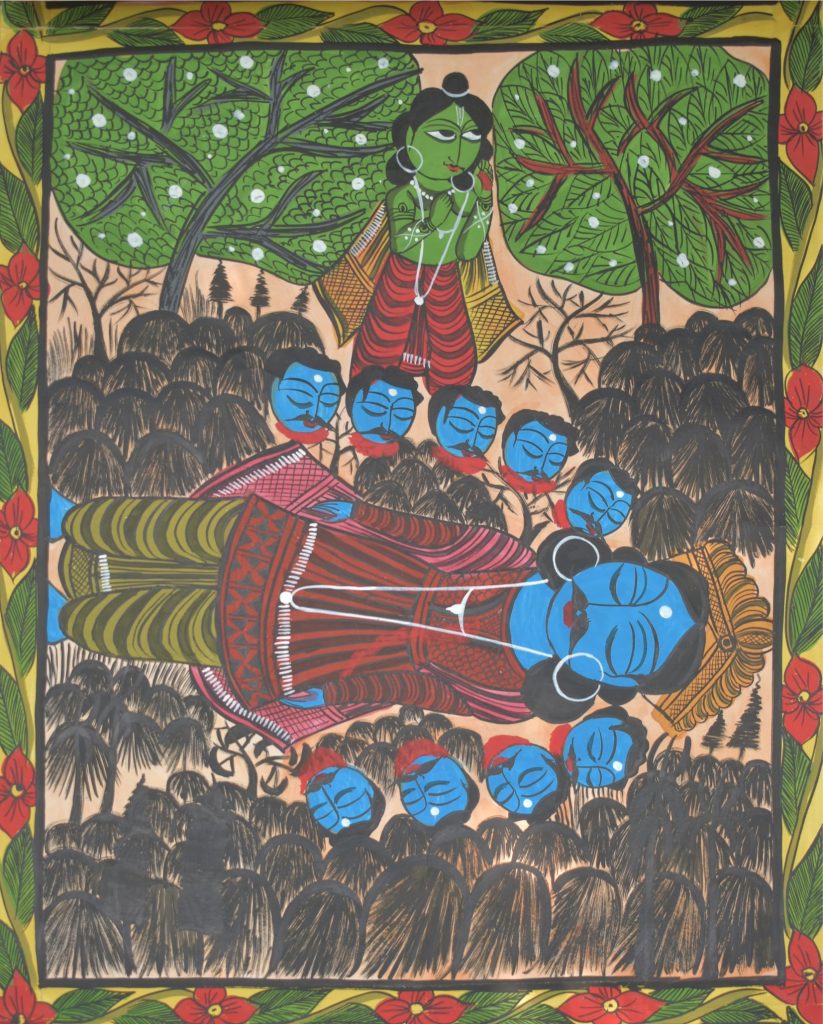

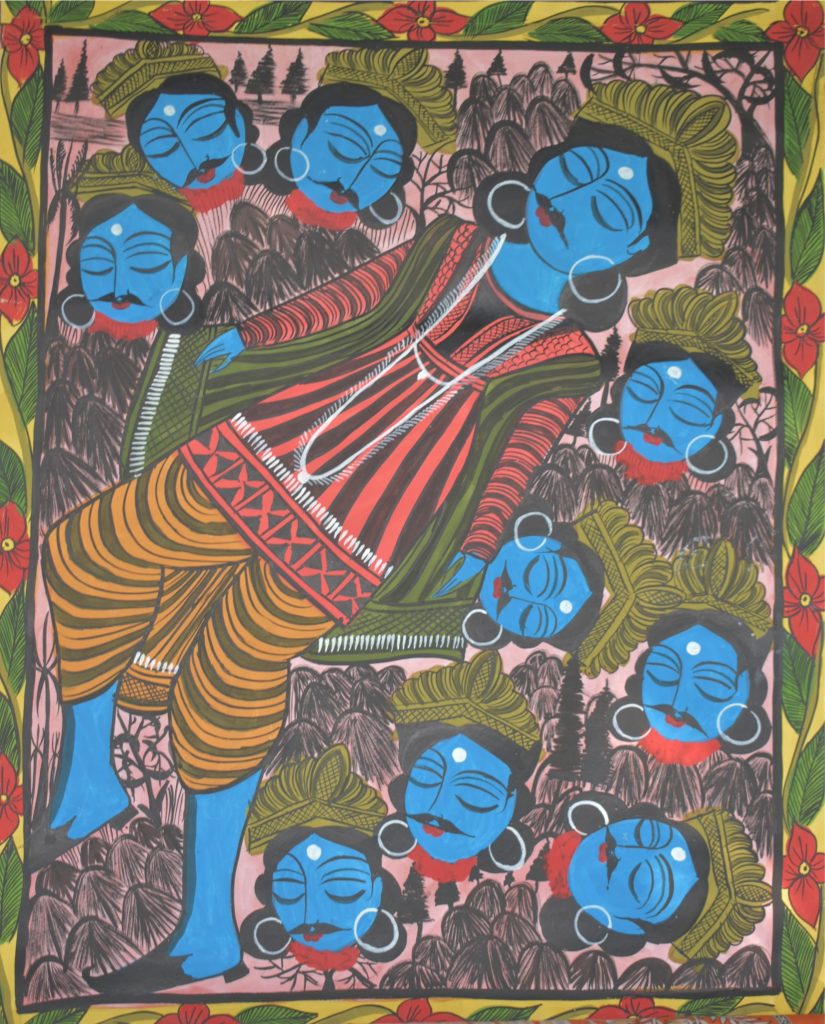

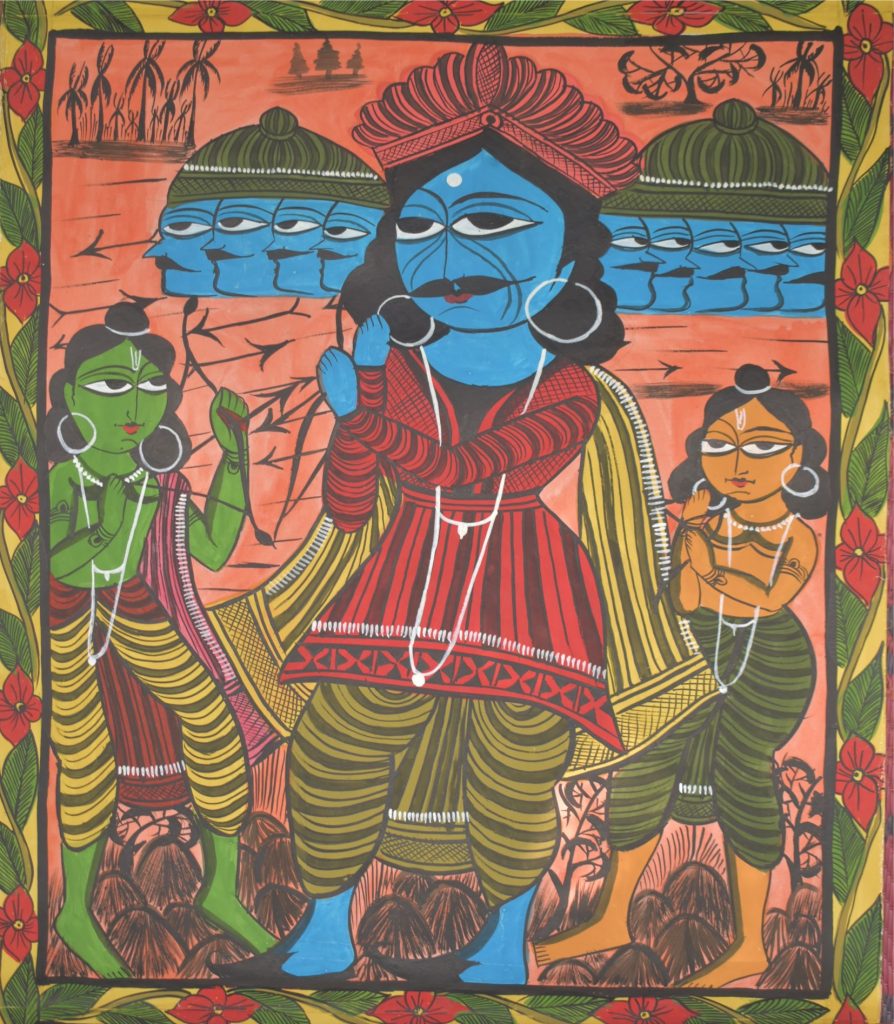

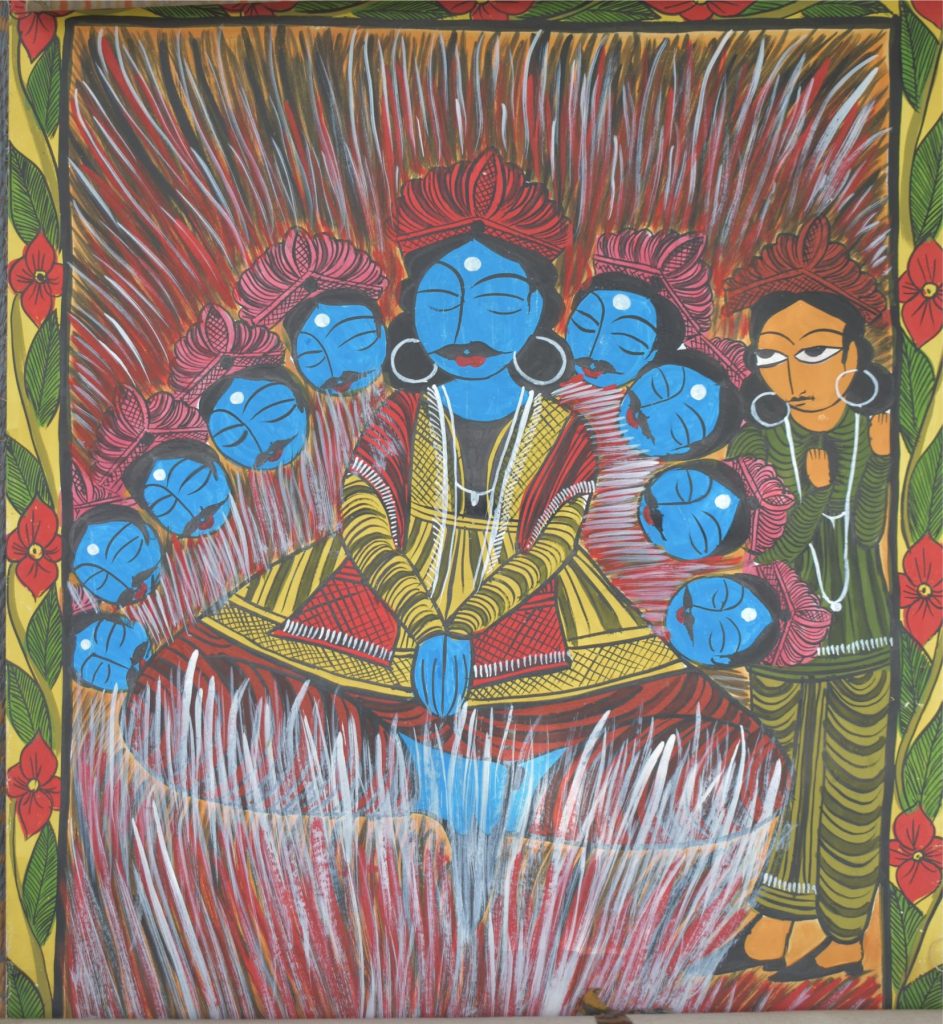

We still paint on mythological themes like the Ramayana and the Mahabharata.

Those patas are still there.

But usually those patachitras are showcased during fairs, or some art exhibition.

For instance, there’s an exhibition going on at the Rabindra. Bharati University and there I have submitted a few patachitras.

Interviewer (TM): Which patas have a greater market value – the mythological ones or the ones based on social contemporary events?

Yakub Chitrakar: The mythological ones based on the Ramayana,

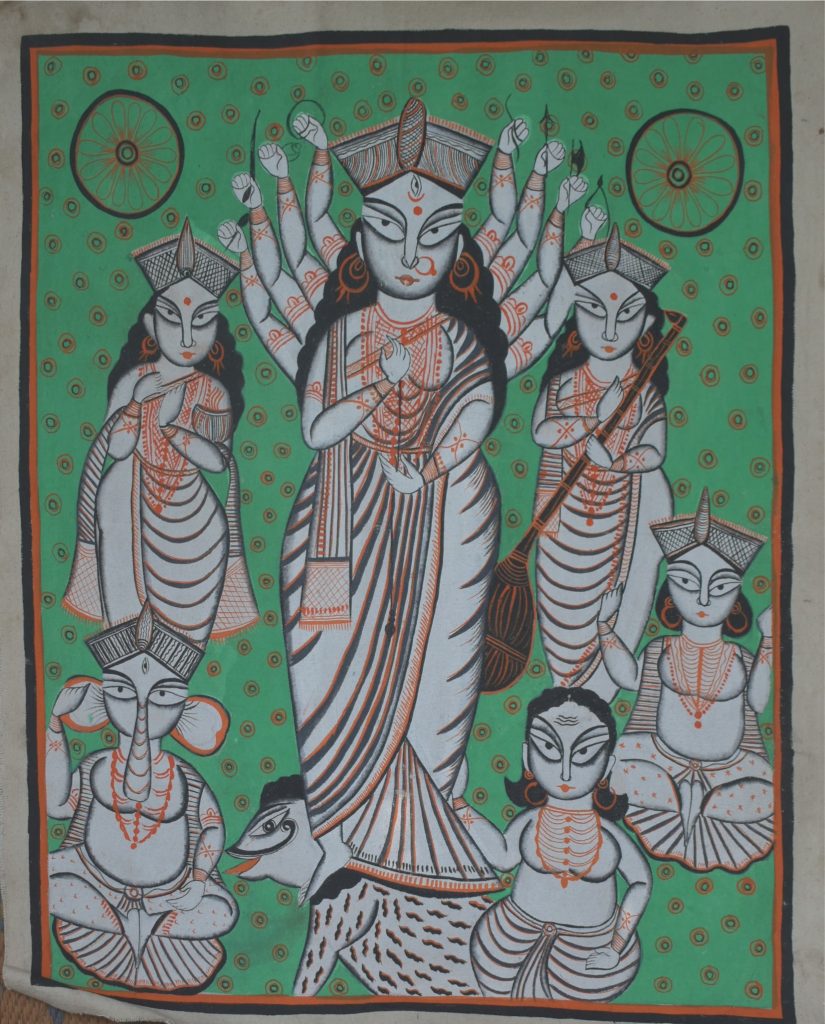

Manasa Mangal, the goddess Durga have a comparatively higher demand in the market.

Interviewer (TM): The songs that accompany these mythological patas have been handed down to you by your forefathers. Right?

So, with time, has there been any revision in the songs – be it in the lyrics or the tune?

Yakub Chitrakar: Yes, a lot of changes have crept in.

Earlier, patuas used to wander about villages, singing songs, without the accompaniment of any musical instruments.

But these days, musical instruments are being played alongside.

There are people who come and request us to sing in that manner.

So, we have had to change ourselves with changing times.

Along with painting, you also compose songs.

Interviewer (TM): You don’t just write the lyrics but also decide upon the tune.

Yakub Chitrakar: Yes, we paint, compose songs as well as sing.

Interviewer (TM): Has there been a revision in the lyrics? For instance, when you compose on mythological themes,

like the Manasa Mangal or the wedding of fishes, do you notice any change in the lyrics of the songs?

Yakub Chitrakar: No, there has been no change in that area.

The Manasa Mangal has always had the same story, the same song and the same lyrics.

Similarly, the Ramayana has been depicted through the same storyline, the same song, the same lyrics.

The wedding of the fishes, too, has a similar story but I have penned it down in my own style.

Again, some other patua might have written it in another style.

Even for government policies like the Kanyashree, each patua has a different way of narration.

But it is more or less the same.

So, there might be different versions for social contemporary patas.

Interviewer (TM): Okay, but when it comes to mythological patas, the lyrics have been preserved.

Yakub Chitrakar: Exactly so. The exact lyrics are retained.

Interviewer (TM): This is something that I have heard from other patuas.

Since, patuas belong to a particular religious community but paint images of Hindu deities,

earlier, they often had to hide their true identity or perhaps maintain two names.

Have you had any such experience?

Yakub Chitrakar: What you said is true.

There were times when these things were practised.

I’ll tell you why this happened.

Suppose a patua named Niranjan Chitrakar has a Muslim name.

Or maybe, Bahar Chitrakar has taken up another name – Ranjit. Chitrakar.

There must be a reason why someone did that.

Had we disclosed our Muslim identity, perhaps, we wouldn’t have been allowed to make idols of Hindu deities.

While visiting villages with the scrolls, had we had revealed our real names,

perhaps they would have hesitated to provide us with food.

As a result, patuas back then used a Hindu name to hide their Muslim identity.

This was indeed in practice.

But for the last fifteen – twenty years, we haven’t changed our names.

Now, we use just one name – our real Muslim name.

For instance, my name is Yakub Chitrakar.

I use this name everywhere.

I don’t have any other Hindu name.

I have just one name.

Interviewer (TM): Do you think your next generation would be willing to carry on with this tradition?

Yakub Chitrakar: Patachitra is an art form.

All art forms ought to be preserved.

As I have already mentioned, I have grazed cattle, worked as an unskilled labourer.

Yet, when I would come back home after a tiring day, I would still paint something.

This was my attempt to hold on to this art.

That is why, I keep telling my children that no matter what you do, you have to keep this art, this tradition alive.

Interviewer (TM): Coming to patas on social contemporary events, there are many people who claim

that some of the patas are their unique creations.

For instance, someone just said that the tsunami pata was first created by him/her.

Another person claimed that the pata on the demolition of the World Trade Centre was first created by him/her.

Is there any such pata, whose theme you came up with?

Yakub Chitrakar: I have a pata on addiction.

That was exclusively my idea.

Interviewer (TM): Okay.

So, you were the first to come up with the topic?

Yakub Chitrakar: Yes.

After you created a pata on that topic, did anyone from your community follow you?

Yakub Chitrakar: No, this has been solely my creation.

If you could please sing a few lines on the composition of that pata.

Yakub Chitrakar: Okay.

Let me tell you something about the song then…

Getting addicted, and trying to quit it are both equally bothersome.

Getting addicted, and trying to quit it are both equally bothersome.

Addiction has harmed men in a thousand unknown ways.

Gentlemen, kindly don’t indulge in such acts.

Listen ladies and gentleman,

Listen to what I say…

I am going to talk of the harms of addiction.

Alcohol, drugs and gambling go on day and night,

They are not even thinking what might happen to them in the future.

There was a zamindar from Raipur.

He lost all his wealth because of addiction, and became a nomad.

They were a happy family of three.

But the company of his friends ruined his life.

Two of them went to Ram’s house to get intoxicated.

After getting drunk, they came back.

There was a zamindar from Raipur.

He lost all his wealth because of addiction, and became a nomad.

Not content with just alcohol, the zamindar started indulging in heroin.

Once these drugs enter your blood, you’ll become frail.

Before consuming these, a person remains sane and sober.

After consumption, he initially feels exhilarated.

Two friends are taking drugs, sitting beside a bungalow.

Intoxicated, they say that they’ll move the bungalow with bare hands.

So, they take off their shirts and throw them on the ground.

Inebriated, another friend walks into the scene.

He sees the other two trying hard to push the bungalow.

So, he runs away with their clothes.

After that, one friend goes back home.

Hearing his wife’s nagging, he slaps her.

The slap was so hard that she lost her life.

Montu realizes his mistake and starts wailing.

These incidents have become so common.

How many more would lose their lives, I wonder.

They die because of their own failings.

No one else is to be blamed.

Here, my patachitra on drug addiction comes to an end.

The patua is Yakub Chitrakar, Naya, Paschim Medinipur.

So, this is how we compose pata songs on contemporary social events.

The government has also deployed us to promote awareness amongst people regarding addiction.

Whenever a new policy is launched, we are asked by the government to create patachitras and raise awareness.

Interviewer (TM): Okay.

So, you are deployed by the government?

Yakub Chitrakar: Yes.

We are put into action by the government to compose songs on such policies.

Interviewer (TM): In these cases, you go back to your former tradition,

where you compose the songs first and then go about spreading the word.

Yakub Chitrakar: Yes, of course.

Those are there.

People are saying that they have seen so many patas about gods and goddesses.

But they are curious about the social changes that get depicted in patachitra.

This is why we have to compose such songs.

Interviewer (TM): If you could kindly shed some light on how patachitra began.

Yakub Chitrakar: As I have already mentioned, thousands of years ago, people used to create paintings using vegetable dyes.

Interviewer (TM): But what were the main themes?

Yakub Chitrakar: The topics usually revolved around Muslims, like Satya Pir,. Gaji Pir, Manik Pir.

The lives of Pirs were painted and then these people used to visit houses and sing songs.

Muslims loved listening to patas that revolved around such topics.

So, they thought that the Muslims do understand the story of Satya Pir but Hindus aren’t able to grasp the meaning.

They realised that if they could start painting on themes related to the Hindus, then they, too, would be interested.

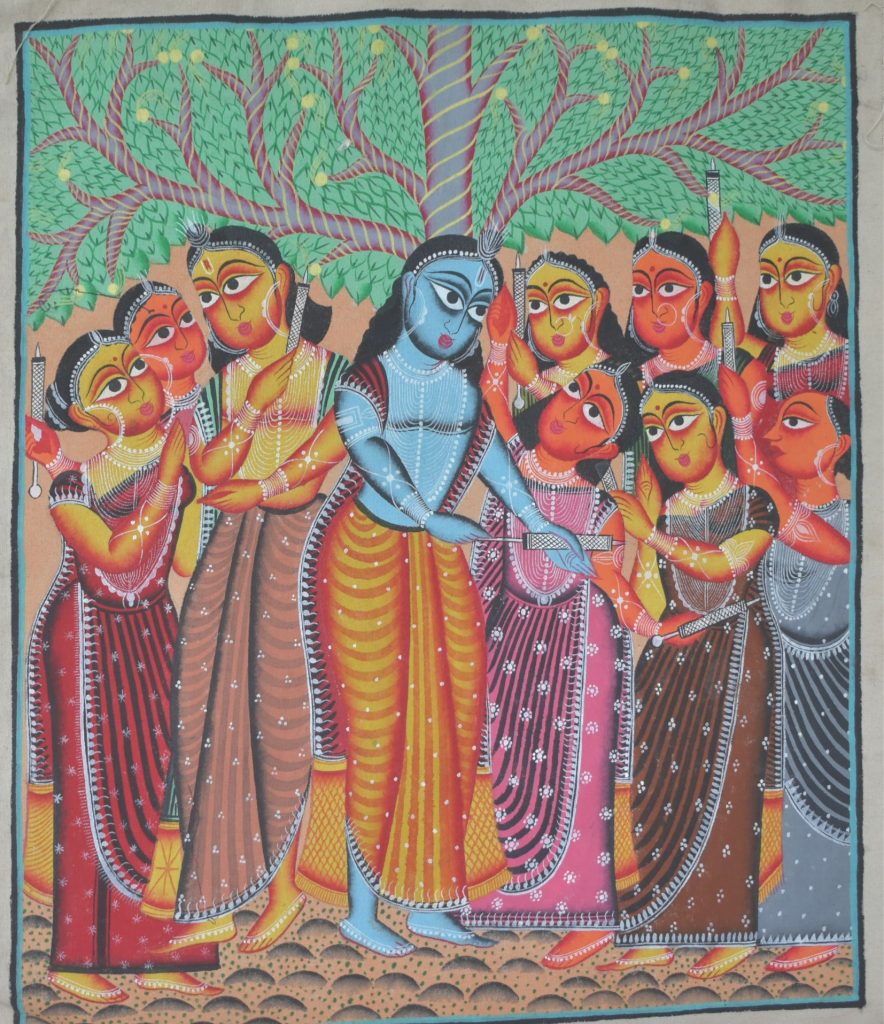

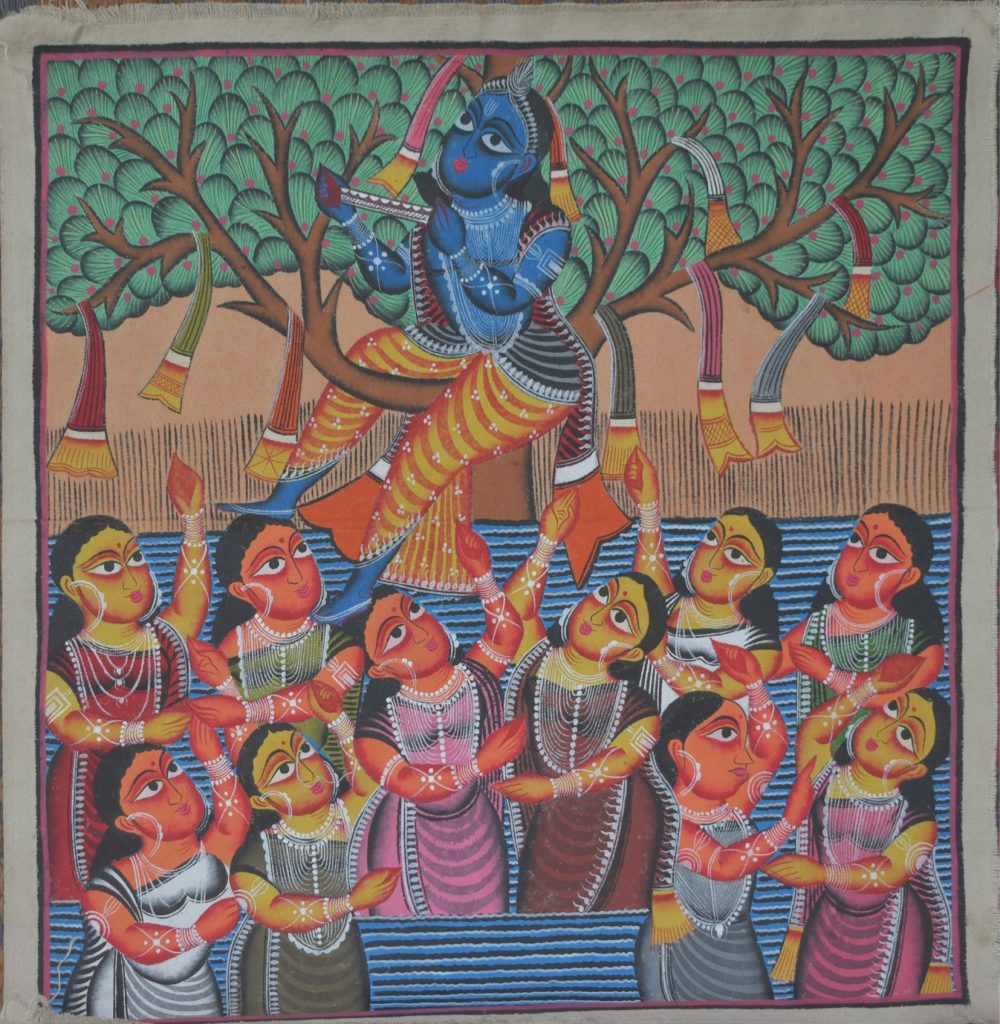

That is when they started composing patachitras on Manasa. Mangal, Krishna Leela, the Ramayana, Nimai Sanyasi.

Having composed such patas, they went over to Hindu homes and told them they had composed new patas

keeping their interests in mind.

The Hindus were impressed and expressed a keenness for such patas.

That is when they started making two kinds of patas – one for Muslims (meant for earning) and the other for Hindus.

Even till this date, we paint two kinds of patas.

We paint on Satya Pir as well as on Hindu goddesses like. Manasa and Durga.

We paint both.

Interviewer (TM): You are painting on Durga and Manasa Mangal.

But how did you get to know of these stories?. Since how long have you known such stories?

Yakub Chitrakar: Stories like the Manasa Mangal, the Ramayana, Durga – they have all been passed down by our predecessors.

My grandfather had learnt from his father; my father learnt from my grandfather; and I am now teaching my children.

This is how the tradition has been kept alive across generations.

The same lyrics, the same song, the same tune.

Interviewer (TM): Thank you so much.

We would like to have a glimpse of your pata on addiction.

Yakub Chitrakar: Should I have to sing again?

Interviewer (TM): No, it’s alright.

You have already sung this once.

What is the theme of this pata?

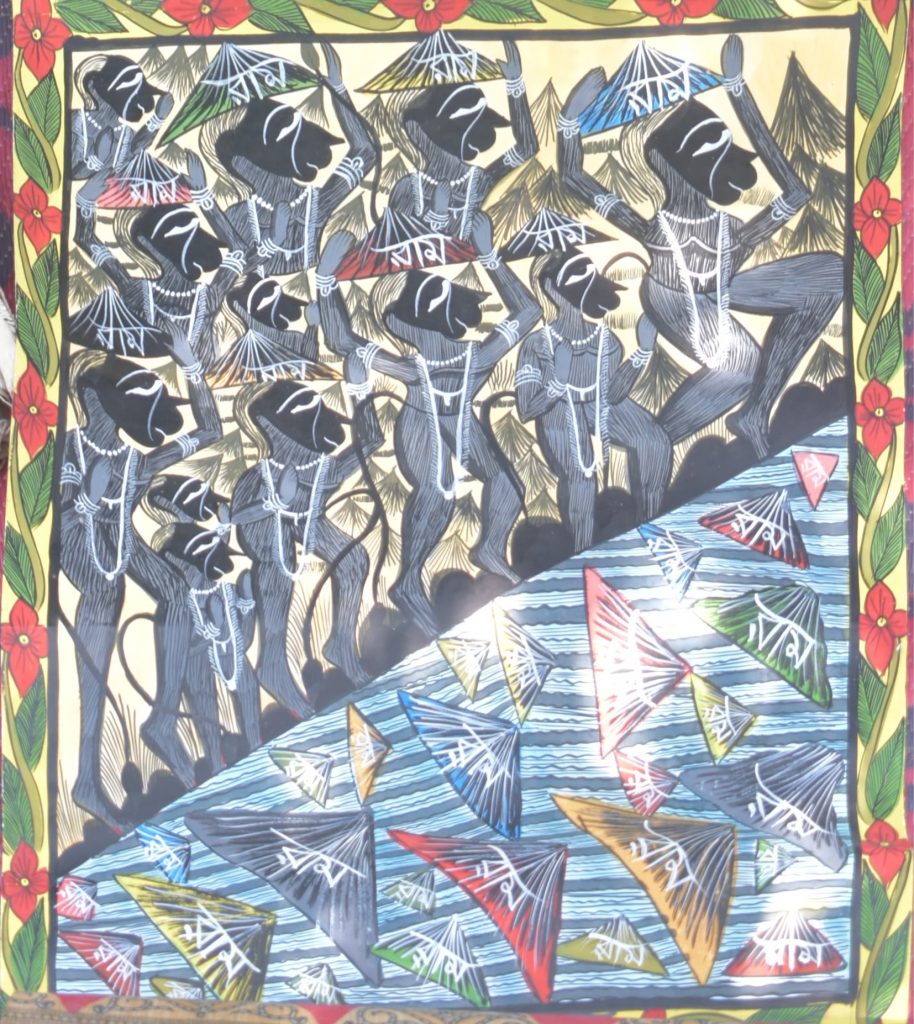

Yakub Chitrakar: This pata revolves around three stories – the Manasa. Mangal, the Ramayana, and Krishna.

Should I start unfurling it?

Interviewer (TM): Sure.

Yakub Chitrakar: The first story is about the Manasa Mangal.

This is where the Manasa Mangal ends and the story on. Krishna begins.

The one on Durga begins from here.

Oh! The story of the Ramayana is also there.

So, it’s basically a pata comprising four stories.

Okay.

The side panels consist of tribal motifs.

So, my pata can be considered to have five stories altogether.

Interviewer (TM): How long did it take you to compose this pata?

Yakub Chitrakar: It took me two months to complete this.

The story of the Ramayana is preferred by foreigners.

This is something that we have noticed.

Let’s not discuss what we did earlier.

But now when we begin painting, we keep this preference in mind.

By foreigners, I mean people especially from Japan, Germany,. London, France.

I’ve been to these places quite a few times.

On visiting these places, I realised that the buildings, there, are huge.

For example, the Nehru Centre – the museum is huge.

In such buildings, these small square patas won’t look nice.

The pata has to match the height of the building and has to run to about a height of a two-storey.

I had carried a few such patas when I went there, but even then, they were not long enough to touch the ground.

That is why we compose long scrolls for customers abroad.

But does that mean that they do not buy small patas? No, they buy these small patas as well.

But we are aware that they usually look for long scrolls and that is why we compose long scrolls for them.

Small patas are also made.

For people in India, we compose patas of varying lengths.

But the long scrolls are not that long!

It is resized into relatively smaller lengths, so that they can be framed and kept as wall hangings.

That is why we make relatively smaller patas for the. Indians, whereas, we make long scrolls for the foreigners.

We compose both long and small patas.

Interviewer (TM): It seems that the Ramayana is preferred to the Mahabharata.

Yakub Chitrakar: Yes.

When we read the Mahabharata it seems baffling at times.

But the Ramayana is not like that.

I mean the story is not that complicated.

Therefore, people find it easier to understand the Ramayana.

To be honest, even I find the Mahabharata very confusing.

The Ramayana can be understood easily.

But it’s not the same with the Mahabharata.

So, we have to compose patas in both the ways.

Moreover, we have to be updated about current affairs – about everything that’s happening around.

We have already composed patas on topics like the tsunami, the 9/11.

We are now looking forward to new events, revolving which we can compose new patas.

We are experimenting with the painting styles as well.

These days, even shoes are being painted on.

Pants, shirts, t-shirts – everything is being painted on.

Shoes are also being painted on.

We are considering the various other media that can be painted on.

There was a time when patachitra was not this popular but now it has earned a world-wide repute.

I remember this incident vividly…my father was alive back then, and I was a mere child, perhaps four-five years old.

A person from London had come down to India.

He liked the Indian culture and wanted to explore further.

(Silence! Please don’t shout)

My father used to compose long scrolls and sing pata songs back then.

My father’s contemporaries also composed long scrolls, wandered round villages, displayed them and sang pata songs.

Once, a patua brought a foreigner to our village.

I used to live in Hobichak then.

They stared at him in amazement and wondered who was that tall, extremely fair man?

Obviously no one from our village had ever seen a foreigner.

We did not even have televisions.

Radios existed, but none of us owned any.

We were all wondering at his complexion and his height.

He had worn shorts.

The Bengali man who was acting as a translator said that when the foreigner had asked him about Indian culture,

the first thing he had mentioned was Bengal’s patachitra.

They wanted us to show them some scrolls.

The Bengali man requested us to bring our patas.

All the patuas displayed their respective patas.

Most of the patas were very old and were in a dilapidated condition.

The foreigner saw all the patas.

His name was David.

He asked the translator if the patuas were interested in selling their work.

The Bengali man conveyed to us that the foreigner was interested in buying our patas.

We were surprised to learn that he was interested in buying these pata paintings made on paper.

He wanted to take them back to London.

He wanted to know the amount he would have to pay for the patas.

We were taken aback at his proposal.

How could someone think of buying such papers which were in such a dilapidated condition?

We said we’ll be happy with whatever he offers.

The foreigner readily agreed to it and bought all the patas.

So, he bought the patas and carried them back to London.

From there, he contacted the Bengali translator and asked him to request us to compose new patas.

Whatever pata we had, was already bought by him.

He wanted us to compose fresh patas.

He said that he had displayed our patas, and had narrated stories about us.

It is recently that patuas are visiting foreign countries and displaying their own work.

But at that time, the scenario was completely different.

Mr. David further added that he had told everyone about our use of colours as well.

The people who had seen our work and had heard our stories were extremely delighted.

They were also quite eager to buy and collect patas.

Mr. David said that the patas he had taken back had been curated in a museum.

He, therefore, wanted us to make fresh patas.

The Bengali man conveyed the entire conversation to us.

That is how patachitra gradually earned a worldwide repute.

The huge popularity was not created in a day.

Patuas have become immensely popular now.

They are recognized everywhere.

But patuas had to struggle hard to hold on to this tradition.

Our children won’t have to face all those challenges that we did.

A market has already been created.

We keep stressing one thing… we must hold on to this art form.

No matter what profession one engages in, s/he cannot let go of this tradition.

As mentioned earlier, I have been into multiple occupations, but at the end of the day I never forgot to paint.

I came back home and practiced patachitra during the evening.

At one point of time I felt like quitting patachitra.

But all of a sudden, I received a phone call, where a person asked me if I was willing to work in his film.

I was surprised and asked him if he wanted me to act in his film.

He said that the movie revolved around patachitra and he wanted me to be present there.

I agreed.

The film was shot at Purulia.

The name of the movie was Shilpantar.

Apart from that, I worked for several other films as well.

So, that movie (Shilpantar) revolved around a house which had patachitra painted on all the four walls.

I painted those patas.

The protagonists were played by. Mr. Subhashish Mukherjee, Ms. Deboshree Roy.

There were several other artists as well.

I got pretty amused that I got a chance to work for a film.

Initially, I was a bit skeptical.

I wondered at my luck and thought to myself whether I really got such a huge opportunity to work for a film.

Then I visited him.

I was told that I had to put up at Purulia for almost a month.

I had to paint and all.

I accepted the offer.

I thoroughly enjoyed the experience.

The film was released in Europe.

Unfortunately, the director (who was pretty young), late Mr.. Bappaditya Bandopadhyay has passed away.

I have worked with him in two-three other films as well.

I have also worked with the veteran actor Mr. Soumitra. Chattopadhyay.

I have worked with several other people on topics revolving around patachitra.

I feel happy and content that I have been able to portray patachitra on the big screen.

Quite often, I discuss these with my sons.

Even if they get a white-collar job…

We are uneducated and poor.

We are not rich enough to travel to foreign countries at our own expenses.

I have travelled far and wide only because of my art work.

The only reason I could visit places was because of my identity as an artist.

Now, we are being nominated and sponsored by various organizations, by the government and also by some billionaires.

But had we not practiced this art form we wouldn’t have been nominated.

I keep telling my sons that no matter what you do please do not abandon this art form.

Do not abandon patachitra.

Even if you are engaged in a different trade, try practicing patachitra when you come back home in the evening.

You need to practice painting, and compose songs.

You need to be aware of the contributions that our generation made, where we had started from,

and why we had started practicing this.

What was the purpose behind this?. You need to learn all these things from us.

I know all these things only because I had learnt them from my father.

If you don’t learn them now, you won’t be able to answer if someone comes up and asks you

about the origin of patachitra.

You can’t say that because you are practicing this art form.

Quite often, journalists ask us how despite being Muslims, we have learnt songs about Hindu deities.

They pose questions on our religious identities.. They ask are you Hindus or Muslims?

I tell them that they must have heard about Lalon Fakir.

We are like him.

We cannot be judged on parochial parameters like religion, caste and creed.

We visit temples, but we don’t worship Hindu deities.

But we paint.

We make clay idols.

In fact, we make idols of goddess Durga.

But we don’t worship.

The pata songs that we sing are not my composition.

They have been composed by our predecessors, thousands of years ago and have been handed down to us.

Some Muslims looked down upon us as we painted Hindu deities, despite being Muslims.

In fact, they didn’t marry their daughters into our community.

We also did the same.

We had a different reason, though.

Our daughters have learnt patachitra from us, but they won’t be allowed to practice it in their in-law’s place.

They won’t let her engage in this art form ever again.

Then what’s the point of learning an art form after so much of hard work? They won’t be able to hold on to this.

If she steps into such a family, the art form would cease to exist.

This is why we don’t want our daughters to get married to anyone from that community.

We don’t have any other reason.

That is why we don’t marry our daughters to members from the. Muslim families.

But now things have changed.

They are willing to get their daughters married to people from the Chitrakar community.

But why now? There was a time when you people looked down upon us.

Then, why this sudden change?

They would say that they were ignorant and also accept that the patuas are widely acclaimed.

So, it is for our growing reputation that you people are finally willing to get your daughters married to members

from this community?

My daughter-in-law is from a Muslim family.

She is now practicing patachitra.

The Muslim community had a condescending attitude towards us at one point of time.

But that discrimination doesn’t exist anymore.

We are all equals now.. No one says otherwise.