Transcript

Shyamsundar Chitrakar:Do you know who that is? That is Kalidas.

This is how the song goes.

Kalidas was a fool.

But with the blessings of the goddess of wisdom, Saraswati, Kalidas became a learned man.

Listen everyone…. That is why education is important.

Why would you rather be blinded by ignorance, people?

This was about the goddess Saraswati.

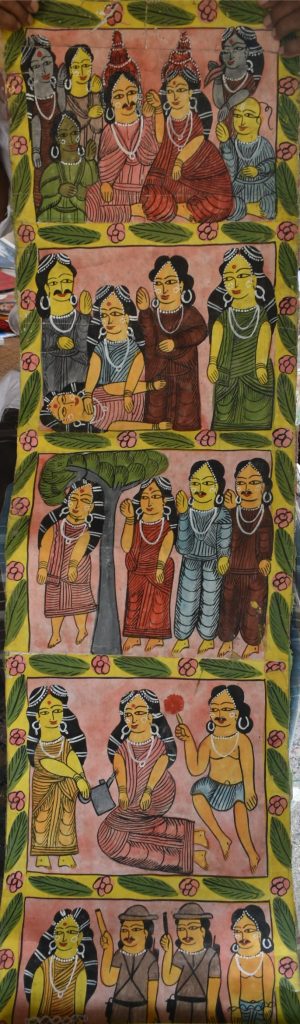

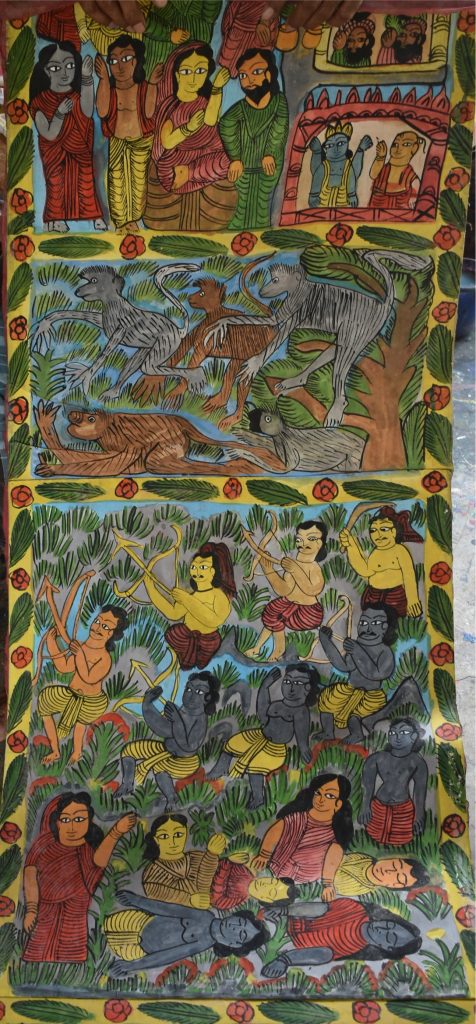

This pata is about Chaitanyadev.

This revolves around the moment of his renunciation of all worldly pleasures.

If you knew you would leave me, O husband…

Why did you then marry me and bring me into this household?

Saying this, Bishnupriya unties her hair and wails at her husband’s feet.

All these patas have a song accompanying them.

This one is about Ravana and Sita.

Students like you come down to Naya and ask questions about patachitra.

They paste these patas on their notebooks.

They buy these small square patas.

Interviewer (RN): Do you sell these patas?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: Yes, for thirty rupees each.

But this discounted rate is only for students.

For others, the rate is fifty rupees per pata.

Take a look.

I am an elderly person. I cannot travel far and wide to sell my patas.

I’d be happy if you would buy a few patas.

I am eighty years old.

An old man cannot travel around much.

Interviewer (RN): What does one do with these small patas?. Are they used as wall hangings?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: No, these are meant to be pasted on notebooks.

Don’t you know that? Students often come down to this village in order to gain knowledge about this art form.

They buy these patas and paste them on their notebooks.

We have plenty of visitors from Kolkata.. They buy these a lot.

Rani Chitrakar: The longer patas are used to adorn houses.

They are also used as gift items.

Interviewer (RN): Have you composed these songs all by yourself?

Rani Chitrakar: No, these songs have been passed down by our predecessors.

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: They have been handed down by our forefathers.

This has been going on for decades.

Rani Chitrakar: These were composed long back.

These small patas are composed by us, but not the longer ones.

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: They were all composed by our forefathers.

Rani Chitrakar: These patas narrate stories of earlier times.

Yes, that’s true.

They are all age-old tales.

These were all composed by my father and grandfather.

Interviewer (RN): How long have you been living here?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: Here? The patua settlement here…

Initially, there was no patua settlement here.

Rani Chitrakar(to Shyamsundar Chitrakar): Tell them about your work, about how long you have been working as a patua.

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: Okay. You wanted to ask her (Rani Chitrakar) a few questions. Right? You may do that.

Interviewer (RN) to Rani Chitrakar: I had the same question for you too.

Rani Chitrakar: I was just five years old when I started working as a patua.

I have been painting, wandering about villages displaying my patas, and singing pata songs since then.

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: When I go around villages, I use a bag. Look at that bag over there.

This is how we carry our patas.

Interviewer (RN): What is this pata about? Who are the characters?

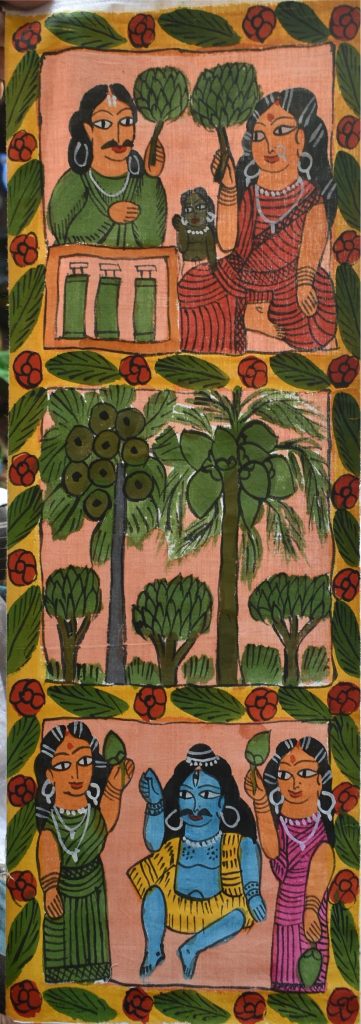

This is about afforestation.

Rani Chitrakar (to Shyamsundar Chitrakar): Why don’t you sing the song from Manasa Mangal?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: When we go around villages, this is where we keep our patas.

Interviewer (RN): Do you compose patas on contemporary social issues?

Or do you paint only on the themes that you had learnt as a child?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: No, I have been carrying on with the themes that I had learnt earlier.

Look at our work. I don’t want to change the subject matter and introduce something new.

The mythological stories have to be held onto.

Listen to these songs now.

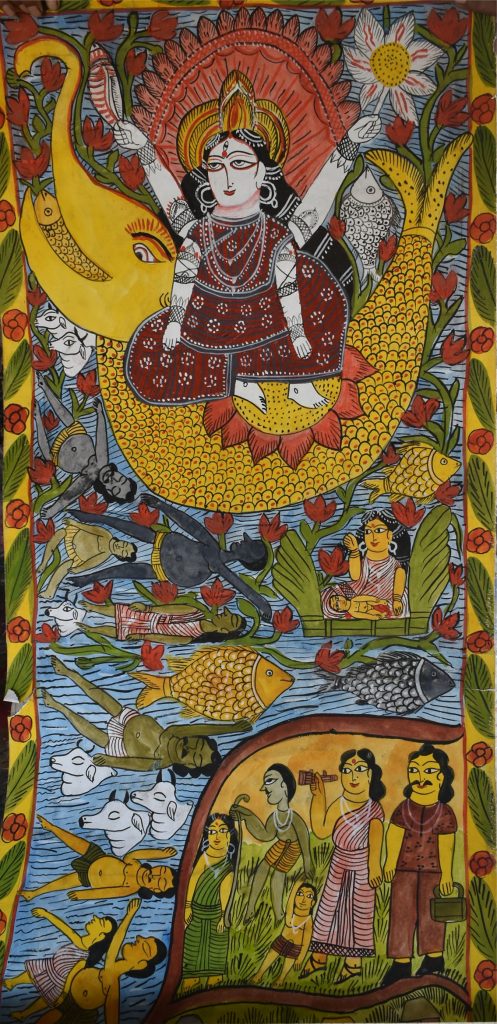

This one is on the Manasa Mangal.

All hail the goddess of snakes, the protector against snake bites.

She was born in a lotus and snakes were her pillows.

Snakes formed her bed and her throne.

Snakes formed the seat of the goddess to be worshipped.

The merchant Chand Sawdagar (an ardent Shiva devotee) started twisting his beard.

He said that he would not cast even a side glance at the snake deity.

He further added that if he were to find any snake sneaking inside his household,

he would kill it and shred it into pieces.

Hearing this enraged goddess Manasa and in a fit of fury she killed all the six sons of the merchant, Chand Sawdagar.

Having lost their husbands, all his six daughters-in-law became widowed.

But even then, the merchant did not shower a single petal at the feet of the goddess.

Every pata is accompanied by a song.

This was a mythological pata.

Let me now sing one on a social issue.

I have already shown you a few small patas.

This is a pata on a social issue.

We used to go around villages displaying these patas.

We learnt the art from our parents and grandparents.

Interviewer (RN): Have the number of customers of patas increased now?

Or has it remained just the way it was earlier?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: No, when I was around fifteen or sixteen (or perhaps, eighteen), people did not buy patas.

They only listened to the pata songs and gave us a few pennies.

We used to wander around with this bag on our shoulders singing pata songs. That is how we earned our livelihood.

But they didn’t buy our patas.

But now, apart from listening to these songs, people are also interested in buying the patas.

There are very few patuas now who visit villages to display their work.

Earlier, we used to carry these bags while going around villages.

Nowadays, these bags don’t exist anymore.. You would find very few patuas having these bags.

However, I still visit villages. But the young generation doesn’t wander about villages, like we did.

Do you think young people like you would be willing to go around villages? Of course, they won’t.

Earlier, people had to battle abject poverty.. They had to undergo a lot of suffering.

That is why they travelled to distant villages in the hope of earning a little money.

Interviewer (RN): Are you the eldest member of the community?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: Well…yes.

Interviewer (RN): What is your name, by the way?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: My name is Shyamsundar Chitrakar.

Where were your parents from?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: My parents have passed away long back. They lived in Tamluk.

There are a few patuas living in Purba Medinipur as well.

Do you have any relationship with them?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: Purba Medinipur was our native place. All the patuas living here have migrated from Purba Medinipur.

Interviewer (RN): Do you only paint on mythological stories and certain social issues?

Don’t you paint on contemporary issues?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: Yes.

Rani Chitrakar: Yes, he paints on a variety of themes.

He has painted on the government policy Kanyashree, AIDS, pollution…

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: Yes, I have worked on topics like diarrhea, malaria etc.

Rani Chitrakar: Yes, we work on a variety of contemporary social issues.

For instance, we made a pata on the tsunami.

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: We have pata on floods. That is a pata on floods.

Rani Chitrakar: Mythological patas have always existed.

As and when certain incidents take place, we compose patas on those issues.

Now, that is a pata on the Mahabharata.

Interviewer (RN): Do mythological patas fetch more customers?

Rani Chitrakar: People who buy patachitra with the sole motive of conducting research, prefer mythological to social patas.

They analyze the language, the techniques.

But people who are more interested in adorning their houses,

or perhaps in gifting it to someone else (a minister, or a teacher),

would prefer a pata on the Santhals (pata on the tribals), or on the wedding of the fish.

The mythological ones are usually bought for research purposes or for curating in a museum.

People from foreign countries prefer mythological patas.

Interviewer (RN): How much do the women contribute in patachitra?

Is their involvement in the art at par with those at men, right from childhood?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: Girls in their childhood used to paint very sparingly, simply because they were not allowed to paint at home.

For instance, at one point when we were younger, patachitra had all but disappeared.

The children of the people who left pata art to explore another line of work do not know the songs well.

And how could they?

Their parents became various kinds of shopkeepers, and now they have branched out into very different lines of work.

But our parents, who held on to this line of work,

didn’t go into another occupation.

They went wandering around villages, displaying their pata art to the people.

When they used to visit villages, we accompanied them to sing songs with our fathers.

After my father passed, I learnt songs from my mother.

But earlier I used to accompany my father on these trips, which is why I have retained all these mythological songs.

At that time social contemporary patas were not made.

Mythological tales like munificent Karna, Savitri-Satyavan, Manasa Mangal, the abduction of Sita from the Ramayana,

the construction of Rama Setu – such and various other mythological songs have stayed in our memory by performance

My father used to perform these songs, as did I as a child.

It is now that we are making new songs for social causes.

Someone asks us to compose a song on Kanyashree, Yuvashree, HIV/AIDS, afforestation, etc.

then we oblige and compose on these topics.

We also compose our own songs for awareness on any natural calamity, like cyclone, tsunami, etc.

and paint patas on the same.

We also have all our old patas. We haven’t forgotten the old songs.

But the new generation of Patuas can paint the new patas, like those on the Santhals, but don’t know the songs.

Interviewer (RN): At this time, how many artists live in this village who are actively pursuing patachitra?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: I think around 50-100 of them live here.

Interviewer (RN): Do you think the number will increase or stay the same in the coming future?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: What does increase mean? The number of paintings may increase, but the number of people singing the songs won’t.

A song needs to be learnt. Anybody can paint, even you can.

But not everyone has been able to learn the mythological songs.

They learn it today but forget tomorrow.

They have put more emphasis on the details of painting.

For instance, earlier, schoolchildren used to be taught things in the right manner, going from beginner to advanced.

There was a training camp held recently, where no such order of difficulty was followed.

There, teenagers learnt those things, but soon forgot everything.

They cannot even sign their own name, how would they manage?

I was a teacher before.

That aside, everyone can paint today, but composing and singing songs is difficult.

Wandering from village to village, singing songs –

I have about a thousand songs memorised.

We know the mythological songs by heart –

but those are not known to the younger crop at all.

But there must be young artists who can compose modern songs using contemporary lyrics.

They are painting contemporary patas, sure.

But they do not know the pata songs.

They could compose their own songs with their own lyrics, couldn’t they?

No, they won’t be able to.

Not everyone has been able to compose their own songs.

We have been able to compose our own songs, but not everyone can.

When we train the new patuas,

Suppose I am given the task under a programme to train people for 6 months on the art of patachitra,

when I teach patachitra to a class of 15 or 30 students at a time,

1 or 2 from those classes actually learn how to sing songs.

2 or 4 perhaps.

That is the rate of learning songs.

I was a master trainer some time ago.

We used to teach basic painting and songwriting to the pupils.

After that, suppose 3-4 months later, having not been to villages to perform their songs,

they invariably forget the songs.

More often than not, they know only the fish pata song.

Everyone knows that song.

What is the fish pata?

The marriage of fishes.

Let me sing a part of it to you.

The mythological songs are somewhat in their memory.

Especially ‘the marriage of fishes’.. It goes something like:

(indistinct chatter)

Let’s attend the wedding of the Dariya fish, o Rangeela

Let’s attend the wedding of the Dariya fish, o Rangeela

The carps would carry the palanquin

Let’s attend the wedding of the Dariya fish, o Rangeela

The rohu fish would play the flute

Let’s attend the wedding of the Dariya fish, o Rangeela

The tengra fish would play the harmonium

Let’s attend the wedding of the Dariya fish, o Rangeela

The perch fish would play the drum

Let’s attend the wedding of the Dariya fish, o Rangeela

All the fish would dine at the wedding feast together

Let’s attend the wedding of the Dariya fish, o Rangeela

The barb fish would be the earring

Let’s attend the wedding of the Dariya fish, o Rangeela

The rohu fish would get the sweets

Let’s attend the wedding of the Dariya fish, o Rangeela

The little fish would play the flute

Let’s attend the wedding of the Dariya fish, o Rangeela.

The carps would play the drum.

Let’s attend the wedding of the Dariya fish, o Rangeela.

The boal fish (wallago) threatens to gobble up all the smaller fishes.

Let’s attend the wedding of the Dariya fish, o Rangeela.

This is the pata on the wedding of the fish. A social contemporary pata.

Interviewer (RN): You are teaching patachitra to the children as well.

But what if they want to get educated and pursue a different career?

How would you react to that?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: Look at my granddaughter there. She is three years old.

In fact, she’s even younger.

Even she can sing pata songs.

We want the next generation to hold on to this tradition.

I can speak on behalf of my family.

I won’t be able to vouch for someone else’s family.

Rani Chitrakar: They may pursue some other profession,

but they must carry forward the tradition of patachitra.

We teach our children how to paint patachitras and how to sing pata songs.

They are going to school, getting educated.

But they have to hold onto this as well.

No one would know anything about them, if they decide to quit this profession.

Rani Chitrakar: Patachitra would also become extinct.

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: Yes, and they would not get any recognition, any fame.

If a person decides to get highly educated and then, eventually become a professor at a college.

How many people do you think would know him/her?

But, apart from being a professor, if s/he practices patachitra,

the entire world would know him/her.

A patua is capable of earning world-wide recognition.

But a professor would, at best, be acknowledged by his students and the college staff.

Such is the beauty of patachitra!

We want our next generation to continue doing patachitra.

We are a bit disappointed with them because they might have learnt to paint but haven’t learnt the songs yet.

Let me sing a couple of lines.

I know thousands of such pata songs.

This one revolves around the French Revolution.

Louis XIV was a French monarch.

He was a dictator. His subjects protested and punished his entire family for this.

The queen was very beautiful and lived a lavish lifestyle.

Listen everyone… listen to their story.

The French Revolution was brought about by Rousseau.

We know about the fall of the Bastille.

We, the patuas, know a lot about world history.

The elderly patuas are knowledgeable, unlike the

younger ones who are not even aware of the pata songs.

They know only two pata songs – the wedding of the fish and the Santhal (tribal) pata.

We want them to learn all the songs.

That would help us in the long run.

Look at this. This is a Santhal (tribal) pata.

Anyone can paint the picture, but very few would be able to narrate the story.

What is the name of the great men and women of the Santhals?

What is the name of their guru and their god? How many patuas, do you think, would be able to throw light on that?

These are the images of Santhali men and women.

These are not the images of Santhal gods and goddesses.

But the other mythological patas that we compose

are all based on the stories of gods and goddesses.

An illustrious figure in the Santhal community was Haram. Pilchu.

Marang Buru is the god that they worship.

I had a pata on this.

I can’t recall where exactly I have kept it.

There is an old pata on Marang Buru.

I think I have kept it there.

So, Marang Buru is their god.

He created the world.

At first, fishes and reptiles came into being.

They further believe that an earthworm emerged from the ground and created the world.

Then, from the saliva of three cows (Ayen Gai, Rayen Gai and. Kapila Gai), two worms were born.

From those two worms came two birds.

These birds laid eggs.

From these eggs were born Pilchu Haram and Pilchu Budhi.

They are the great legends in Santhal culture.

It would have been better if I could have illustrated it with the pata.

Pilchu Haram and Pilchu Budhi were the – explaining would be easier with the image at hand.

Elderly patuas know a lot of stories, which the younger ones don’t.

They can all paint but cannot sing.

They have become commercial artists.

But the ones upholding folk art would know all the pata songs.

All these patas have songs accompanying them.

Therefore, several people flock here to listen to these.

You take out any pata and I’ll be able to sing the song accompanying that pata.

Someone might be able to copy my painting.

But s/he would not be able to sing.

Rani Chitrakar: The story that he narrated just now can be seen here.

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: I was narrating the history of the Santhal pata.

This is Marang Buru.

Here are the three cows.

From their saliva, two birds were born.

The birds laid two eggs, from which were born Pilchu Haram and Pilchu Budhi.

Their offspring were named Hora Hopon and Burhi Hopon.

They wandered in forests.

They had seven sons and seven daughters.

These children all got married.

Now, this pata depicts how everyone was celebrating the wedding.

So, the main pata is this one.

That other pata has been composed separately in a frame so as to increase its chance of being sold.

But this is the main pata.

That pata does not have the entire story.

Just look at how long this story is!

Interviewer (RN): Patas might be of varying lengths. Right?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: Yes.

This is the main pata, and that is just a sub-plot of this story.

Not the reverse.

Rani Chitrakar: This pata depicts the entire myth of the origin of the Santhals.

It narrates how Pilchu Haram and Pilchu Budhi had seven sons and seven daughters.

After that, they both passed away and their children assumed that perhaps they were their parents.

They were not aware earlier.

So, all the children completed the funeral rites.

This is the main story.

Towards the end, however, we have another story where a person donates his eyes.

Look at the size of the pata.

Interviewer (RN): These old patas are not put up for sale. Right?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: No, they are sold, too.

Rani Chitrakar: Only people who are interested in such old patas would think of buying them.

One or two such patas get sold.

This seems very old.

Rani Chitrakar: Yes. Some people came from Delhi.

They wanted this to be curated at a museum.

I have agreed to give them two such patas.

If some one asks for it specifically, I give them one or two of these patas.

Interviewer (RN): How is the price determined? The older the pata, the higher the price – does it work that way?

Rani Chitrakar: Yes, the prices are high.

Actually, we are not able to preserve these old paintings.

They were done by our forefathers.

We are poor. What else can we do?

So, when someone asks for such patas, we readily agree.

We sell them for 100-150 rupees.

The rates, however, have improved.

It’s not too high though.

This pata will, at best, fetch us five thousand rupees.

Interviewer (RN): How is the price of contemporary patas determined?

Does it depend on the length of the pata or the quality of the work?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: It depends on the quality of the work.

For instance, a person works on a painting for four days and then invests a month on another painting.

Do you think that the prices for the two paintings would be the same?

For example, I take just one day to paint these patas.

I can paint two patas per day (only if I paint the entire day).

If I can make two patas, I’ll be able to sell them for thirty rupees each.

But a longer pata, which takes around three to four days, cannot be sold at this price.

Interviewer (RN): I noticed that the patas are gradually becoming smaller.

Why is it so? Are the customers themselves asking you to compose patas of smaller lengths?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: The long scrolls are only kept in museums. People prefer smaller patas because of space crunch.

We have long scrolls as well. But people prefer the smaller ones.

Shyamsundar Chitrakar (to Rani Chitrakar): Show them that long scroll.

Rani Chitrakar: We have scrolls longer than this.

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: Yes, we have longer scrolls.

We have scrolls running up to twenty to twenty-five feet.

But in order to adorn houses, the smaller ones are preferred.

Rani Chitrakar: This pata has a song accompanying it.

Look at the small ones. They are meant to be put up in homes.

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: We have long scrolls.

But people don’t have much space in their houses these days.

That is why such small patas are composed.

Rani Chitrakar: It’s convenient to have smaller patas because they can be used as a wall hanging.

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: The longer patas are for the museum.

A museum has huge rooms where they can accommodate such long patas.

Rani Chitrakar: We have scrolls that are longer than this.

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: Yes. We have scrolls longer than this.

Look at this pata.

This is a long pata.

But the episodes have been fragmented into shorter narratives and have been painted on these small patas.

Interviewer (RN): Okay. So, are all the patuas here, followers of the Islamic faith?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: Yes, we are all Muslims.

But we follow a Hindu lifestyle.

We paint Hindu gods and goddesses.

So, it’s natural that patuas should follow a Hindu lifestyle.

Interviewer (RN): Okay. So, you follow a Hindu lifestyle.

But do you abide by certain customs of the Islamic faith?

Or have you stopped following them?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: We follow customs of all religions.

We read the namaz everyday.

But then, there’s just one God.

Rani Chitrakar: Yes, we abide by the customs and practices of our religion.

For instance, when someone passes away, we cremate him according to Islamic rites.

Even when someone gets married, we abide by the rules of our religion.

We keep fast during the month of Ramzan.

However, we are unable to give up the Hindu work that we have been doing for generations.

It is actually forbidden in our religion.

But it is not possible for us to give up our profession.

We have not been able to give it up in the past. Even in the future, we won’t do that.

We have been doing this for ages.

If we quit this profession, how would we survive?

Interviewer (RN): How would you react if someone in the higher religious authority

expressed disapproval of your work and your lifestyle?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: Yes, we had faced severe criticism at one point of time.

Initially, patuas were all Hindus.

They converted to Islam during the rule of the Nawab.

But they were assured that they can continue painting and singing.

That is what we have been following till this date.

Muslims never composed patas.

But the patuas have all converted to Islam and compose these patas.

Rani Chitrakar: Muslims paint as well.

For instance, students of art colleges (who are Muslims) paint.

Not all Muslims paint. But some do.

We have been to the Kala Bhavana (Art College), Santiniketan.

There we met a boy named Shahjahan.

He, too, is a Muslim. But he paints.

In fact, nowadays, many Muslim girls also paint.

They don’t paint patas. Or perhaps, they don’t even compose songs like we do.

But they also paint.

Interviewer (RN): Okay. When a pata is displayed in a fair or an exhibition, it bears the name of the village.

The name of Naya, Pingla is always mentioned.

But does the name of the individual artist get highlighted?

Or is it only the name of the village that gets acknowledged?

Rani Chitrakar: We reveal our identity, only when someone enquires about individual artists.

For instance, you came down to interview us.

Someone must have told you that you can go and interview these people.

But you didn’t know us individually.

You simply came down to a village of patuas.

I came up and introduced myself to you.

That is how you got to know our names.

That is how things work.

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: You’ll show our business cards, our interviews to other people.

Your friends, your professors would eventually get to know us.

People then come and meet us for work or invite us over to their places for work.

If someone requires ten patuas to come over and perform, would only the two of us go there? No.

We’d take along several other patuas from this village.

Interviewer (RN): Okay. So, that means your patas are better known as artists from Naya, Pingla.

The name of the individual artist gets marginalized.

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: No, no. That is not what I meant.

The name of the individual artist definitely gets mentioned.

I’ll be able to tell you who the artist is just at one glance.

We all know the works of the patuas here.

Interviewer (RN): Could you please tell us something about your forefathers?

What kind of pata did your father, or grandfather, compose?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: My grandfather was also a patua.

But we don’t have his patas anymore.

We have sold them. I have also sold my father’s patas.

I was perhaps fifteen or sixteen when I sold my father’s patas.

They have been sold to visitors from foreign countries.

The prices were pretty low back then.

Rani Chitrakar: We still have some patas painted by my grandfather.

I have preserved them. I had sold one of his patas to a customer from Delhi.

That pata is now curated at the Rashtriya Kala Bhavana.

They paid me two lakhs for that.

There are still two-three patas that I have preserved.

There’s one on the goddess Durga.

Interviewer (RN): Did you forefathers visit fairs and sing pata songs there?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: No, fairs weren’t held at that time. They went around villages and sang.

Earlier, we didn’t have all these fairs.

Rani Chitrakar: Patuas used to visit households and sing four or five pata songs.

They were paid in kind – they usually got a measure of rice.

In rural fairs, people sold utensils.

The concept of urban fairs came up perhaps only fifty years back.

Fairs were not organized in urban places earlier.

Interviewer (RN): Your forefathers were not from Pingla. Where did they live?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: They lived in Nandigram and several other places.

They wandered about villages with their patas.

A programme used to be organized where all the patuas would flock together.

Rani Chitrakar: It has been 100-150 years since the patua community settled down here.

Interviewer (RN): Is there any difference between the patas that were composed back then, and the patas that are being composed now?

Rani Chitrakar: Yes, there’s some difference. Nowadays, we compress several episodes within just one frame.

But earlier, there used to be separate patas and separate songs for each episode.

The patas used to be very long.

Spacing was also important.

But now, we try compressing four-five stories within a single narrative.

That is the only difference.

Other than this, there’s no other change.

For instance, Manasa Mangal is a pata that has been passed down by our forefathers.

The songs, the story – everything has remained the same till this date.

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: This is a pata on the benevolent Karna.

The story has remained the same.

Now tell me… where would you keep such a long pata?

Interviewer (RN): Right.

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: You’ll have to keep it furled.

But then what would be the point of buying such a scroll if s/he has to keep it that way?

Rani Chitrakar: This pata depicts how Indra had asked Karna to give away his armour.

He did that so as to be able to protect his son Arjuna from the invincible Karna.

This one is on the Hindu god, Narayan.

He came disguised as a poor Brahmin and visited the family of an impoverished couple.

They didn’t have enough food to offer him.

So, they killed one of their seven sons and offered his meat to Narayan.

Narayan, being pleased by their hospitality, brought the dead son back to life.

This is the entire story.

Earlier, such long scrolls were made because they had to be displayed at villages.

But nowadays, people buy patas to adorn their houses.

That is why patas are being made on smaller sheets.

Earlier, people didn’t buy patas.

But now there are takers for patas.

Interviewer (RN): You mentioned that you have composed patas on the tsunami, on communal harmony.

So, who was the first patua in your community to have composed patas on these topics?

We were the first.

Rani Chitrakar: Yes, we did that all by ourselves.

Interviewer (RN): When a patua paints on a new topic, everyone starts following him/her. Right?

Rani Chitrakar: Yes, absolutely. Often, people hear about a new topic from another patua – – There’s a reason why we started composing on such themes.

Patachitra had almost become a dead tradition.

We were trying our best to revive it.

So, we started composing on themes like afforestation, dowry system –

issues, which could garner public attention.

People started paying us more.

They also started expressing interest in buying them.

Rani Chitrakar: We also started getting invitations to perform at several places.

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: We have composed patas on diarrhea, malaria, HIV.

People are more interested in such patas.

Rani Chitrakar: We often compose songs on current affairs.

These patas are then bought by the people working on such issues.

For instance, there’s an American boy named David and a lady called Jenny.

They are both working on HIV.

They bought quite a few patas based on this particular topic.

They also invited us to several programmes where we had to perform our pata song on HIV.

The villagers then paid us well.

There are certain environmentalists who are interested in our work on afforestation.

They have also bought patas on these topics.

We also earn a few pennies that way.

We paint on policies like the Kanyashree, Yuvashree.

The West Bengal government pays us a thousand rupees for that.

There’s a person from Delhi, who wanted us to paint on the tsunami.

That is when we all made a pata on that.

The Ministry of Information and Cultural Affairs has helped us a lot.

They have been helping us for the last twenty-five to thirty years, in relation to patas.

They also provided us with life insurance policies.

But I misplaced the documents and could not follow it up.

Rani Chitrakar: All the patuas here receive a monthly stipend of a thousand rupees every month.

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: Our Chief Minister has sanctioned this stipend.

There are one hundred and twenty families living here.

That means the government is paying a stipend of one lakh twenty thousand per month.

Rani Chitrakar: This is the only help that we have received from the government.

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: But this has helped us immensely.. It was a blessing of sorts.

Rani Chitrakar: Yes, the Chief Minister has sanctioned the amount. The previous government didn’t.

Shyamsundar Chitrakar:The Ministry of Information and Cultural Affairs has always offered their help.

They appreciate the elders in the community.

They invite us to several programmes.

Earlier, they used to post letters inviting us to exhibitions.

But, nowadays, they call us up.

Interviewer (RN): Could you please throw light on the origins of patachitra.

Have you heard any story regarding this?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: Okay. I’ll tell you about that.

But let us first sing a few pata songs.

I’ll end the interview with that. Listen to the songs first.

Rani Chitrakar: This pata is on the abduction of Sita.

I’ll take out a smaller one.

This one is a long pata.

This is a pata on Radha-Krishna.

Who asks you to fetch water from the Yamuna, after the sun sets?

Who asks you to fetch water from the Yamuna, after the sun sets?

Who plays the flute seated on the branches of the burflower tree?

Who plays the flute seated on the branches of the burflower tree?

Who asks you to fetch water from the Yamuna, after the sun sets?

No one knows that she has fallen for the dark man.

No one knows that she has fallen for the dark man.

Who asks you to fetch water from the Yamuna, after the sun sets?

Who asks you to fetch water from the Yamuna, after the sun sets?

Seated under the shade of the tree, Krishna pulled the end of my sari.

All the women of Braja lost their hearts to this man

Who asks you to fetch water from the Yamuna, after the sun sets?

Someone sings, someone dances, someone else chants the name of Hari.

Radha, lost in her thoughts, rolls over the place.

Who asks you to fetch water from the Yamuna, after the sun sets?

Radha goes to fetch a pail of water from the Yamuna with her veil.

Who asks you to fetch water from the Yamuna, after the sun sets?

Krishna appears mid-way.

Radha, on seeing him, covers her face.

Who asks you to fetch water from the Yamuna, after the sun sets?

Krishna then says, “Why are you hiding your face from me.

You are covering it up with your headscarf.. Are you a precious gem?”

Who asks you to fetch water from the Yamuna, after the sun sets?

Radha says, “I am your distant aunt.

You are my nephew.

Don’t joke around with me, you shameless fellow.”

Who asks you to fetch water from the Yamuna, after the sun sets?

Krishna responds, “Let your husband Ayan Ghosh come over.

I’ll make you realize how mistaken you are.

I’ll make him sell off all his cows.

I’ll make sure his pride crumbles.”

Who asks you to fetch water from the Yamuna, after the sun sets?

Krishna keeps on saying, “I’ll barter all my cows in exchange for you.

Where would I find such an exquisitely beautiful woman?”

Who asks you to fetch water from the Yamuna, after the sun sets?

Radha says, “Why are you proposing to a woman who is already married.

Why don’t you go back home and ask your father to fix your wedding?”

Who asks you to fetch water from the Yamuna, after the sun sets?

Krishna says, “I wanted to get married.

But according to my destiny, I’ll only get married to a woman named Radha.”

Who asks you to fetch water from the Yamuna, after the sun sets?

Radha complains, “Why are you interested in a married woman?. You should go and drown yourself in the Yamuna.”

Who asks you to fetch water from the Yamuna, after the sun sets?

Krishna teases, “Where would I find the money to buy a pot and immerse myself in the Yamuna? How would I buy a rope and hang myself?”

Who asks you to fetch water from the Yamuna, after the sun sets?

After listening to Radha, Krishna chants a spell and his flute turns into a black serpent.

Who asks you to fetch water from the Yamuna, after the sun sets?

The snake coils up at Radha’s ght foot, and bites her on the left one.

Who asks you to fetch water from the Yamuna, after the sun sets?

Radha faints on her way and calls out Krishna’s name.

Who asks you to fetch water from the Yamuna, after the sun sets?

Radha agrees to marry Krishna.

She pleads with Krishna to remove the poison.

Who asks you to fetch water from the Yamuna, after the sun sets?

Krishna removes the poison from her body.

Who asks you to fetch water from the Yamuna, after the sun sets?

Radha regains her consciousness and she wakes up.

The two fall in love and have, since then, become inseparable.

Who asks you to fetch water from the Yamuna, after the sun sets?

Who asks you to fetch water from the Yamuna, after the sun sets?

Look, there’s another small pata on Krishna Leela.

It is difficult to accommodate such a long scroll in one’s house.

That is why we have made this small pata, keeping the convenience of the customer in mind.

Rani Chitrakar: These songs are usually sung in a chorus.

That makes it sound more appealing.

This is a song for chorus.

I performed on a Bengali television channel – Zee Bangla.

There were four or five other patuas singing alongside.

It was only last Friday that I performed there.

Interviewer (RN): Okay. So, if you could please throw light on the origins of pata. We would like to end the interview with that.

Is there anything else that you would like to ask?

Shyamsundar Chitrakar: Have you heard of Vishwakarma?. He used to paint pictures of Mahadev.

That is a story I heard from my great grandfather.

I used to call him Bada Abba.

Do you understand the meaning of that? It means great grandfather.

He used to tell me old stories, which I used to listen to as a child.

So, coming back to the story…Vishwakarma was painting the portrait of Mahadev.

In the middle of that, he went and had some snacks.

Then, without washing his hands, he came back and resumed his painting.

His father was furious to see him resume his work without even washing his hands after his snack break.

Mahadev called him an inefficient son and drove him away.

The youngest ones are usually the most mischievious.

Vishwakarma left silently.

He wandered in forests, ate whatever he could.

In that particular region, lived a demon that devoured human flesh.

The king declared that the person who manages to kill the demon would win

the hand of the princess in marriage and would also be given half the kingdom.

The news of the king’s decree reached far and wide.

Vishwakarma used to paint pictures everywhere.

He used to etch on stones as well.

He etched on a rock with a smaller rock.

Eventually, he got to know of the demon’s existence and the king’s declaration about the same.

He kept asking local people about the whereabouts of the demon until he found the forest where he lived.

Vishwakarma went to that particular forest and started painting the image of the demon on a huge rock.

He hid behind a tree and kept an eye on everything.

The demon came from the other end and seeing another demon (image) in front of him rushed forth.

It started punching the ‘other’ demon and eventually suffered fatal injuries.

The demon actually thought that there was another competitor now and it had to fight the other demon and subjugate it.

That is how it got killed.

Vishwakarma watched everything silently.

He didn’t fight the demon physically but managed to kill it.

He came back after some time and found the demon lying dead.

He then went to the king and narrated the entire incident.

But to verify his own deed,

He asked the king to send his officials, a gunny sack and a weapon.

The king thought that Vishwakarma was lying and refused any help.

Vishwakarma then asked for a weapon and left.

He mutilated the demon, put the pieces in his gunny sack and brought it to the king.

The king believed Vishwakarma was telling the truth about the demon’s death.

When the king was about to offer half his kingdom and his daughter, he politely declined.

Vishwakarma said that the only reward he wanted was an opportunity to establish himself as a patua.

He started painting on leaves (paper didn’t exist back then) and wandering about villages singing pata songs.

Gradually, others started following him and that is how the tradition of patachitra began.

So, he was officially conferred the title of being the only patua in the kingdom –

someone who would wander about singing pata songs.

Earlier, radios or cassettes did not exist.

This was the only form of entertainment for people.

Patuas were invited to entertain people with their paintings and songs.

This is a story that my grandfather had told me.

This is how it got transmitted – by oral means.

Even till this date, that is how patachitra has been surviving.

Right. It is all the same old stories passed down orally.

Yes, it is still the same.

Rani Chitrakar: Even the colours are prepared using age old techniques. They are all vegetable dyes.

Back then, chemicals were not used for this purpose.

For instance, we procure the yellow colour from turmeric.

Yes, we have already seen that.

Turmeric yields this bright yellow colour.

We grind this into a paste and store it in a coconut shell.

We use the leaves of Indian beans for obtaining the green colour.

I have already shown this to you, right?

So, this is the history of pata.

Not everybody is aware of this rich history.

I heard it from my grandfather.

In the same way, I have told the story to my children.

I gladly narrate these stories to people who are willing to listen to them.

For instance, you have taken the trouble of coming down to this village.

We’ll miss you when you go back.

Money is not always the most important factor.

I thank you for coming and listening to all these stories.

Please do come again.

I hope you feel good listening to the history.

Interviewer (RN): Yes.