Transcript

Interviewer (RN): What is your name?

Anwar Chitrakar: My name is Anwar Chitrakar.

Interviewer (RN): How long have you been living in Pingla?

Anwar Chitrakar: I was born and brought up here.

It is here that I received training from my father.

Interviewer (RN): Did your father, too, live in this village?. Or did he migrate from a different village?

Anwar Chitrakar: No.

I have heard that my father used to live in a different village.

Earlier patuas used to wander about villages, displaying and singing about their scrolls.

Likewise, my father, too, at some point of my time, came here along with my grandfather.

Interviewer (RN): How long back would that have been?

Anwar Chitrakar: Many years back.

I am myself forty- or forty-two.

Moreover, I have got older siblings.

So it must have been around fifty to sixty years back.

Interviewer (RN): What is your father’s name?

Anwar Chitrakar: My father’s name is Amar Chitrakar.

Interviewer (RN): Okay.

So, have you ever seen your grandfather?

Anwar Chitrakar: No, no.

Interviewer (RN): In your family, was your father, the eldest member, then?

Anwar Chitrakar: Yes.

Interviewer (RN): If you can please dwell on how patachitra was back in those days.

What kind of patas did your father make?

Anwar Chitrakar: My father used to work mainly on mythological subjects – like, gods and goddesses, the Mangalkavya, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata.

Each work had a certain story accompanied by a song.

One thing that has been continuing for generations is the fact that we prepare our own dyes from various plants, the earth, flowers, fruits.

We mix the resin of the Bengal quince with these dyes so that the colours can be preserved for longer.

This is how my father used to work.

This is how we have been working too.

Interviewer (RN): Okay… so you were telling us about your siblings.

Your brother’s name is Manu and your sister’s name is…

Anwar Chitrakar: My elder sister’s name is Swarna Chitrakar and the younger one is Salma Chitrakar.

Interviewer (RN): Is there a story behind your being named Anwar?

Anwar Chitrakar: No.

Actually, by and large, patuas follow the Islamic tradition.

But, at the same time, they also work for Hindus.

I have heard that earlier there was an issue regarding names.

For example, my father used to make earthen idols of gods and goddesses.

Had he gone to make these idols revealing his Muslim identity, it wouldn’t have been gladly accepted by people.

A Muslim person making an idol of the ancestral god/goddess in a Hindu household! That is why, since then, people started maintaining two names.

Later, people started having just one name, though.

Today, you will see that patuas often have Hindu names.

But again, they had another Muslim name as well.

For example, in a family that had four children, two would have Hindu names, while the other two would have Muslim names.

Interviewer (RN): Okay, coming to these artworks now… do you construct your works mainly on mythological stories or do you focus mainly on social issues?

Anwar Chitrakar: Mythological stories are definitely around.

But we also work on social issues.

Interviewer (RN): In the last fifteen-twenty years, which tradition of patachitras has been more practiced?

If you ask about the last fifteen to twenty years, well…. I’ve been into this only for the last fifteen to twenty years.

What I have observed in all these years is that people definitely appreciate and admire patachitras based on

mythological stories but they are equally fond of patachitras based on contemporary social issues.

Interviewer (RN): So, who exactly are those people? When you wander about places, and exhibit your work indifferent fairs… are those the people you are referring to?

Anwar Chitrakar: No, no.

There were no buyers earlier when people used to just wander about villages, displaying and singing about their patas but just people who listened to their songs.

If they liked the song, they donated something and that is how the patuas earned their living.

But now there’s a question of purchasing artworks.

Besides, we have to perform in cities.

The earlier practice of visiting villages has drastically decreased.

Interviewer (RN): So, the buyers from the cities you are referring to… do they prefer the patas based on social issues?

Anwar Chitrakar: Patuas have always worked on social issues.

Even our predecessors have done that.

The works produced might have been fewer in comparison to the present, when more such works are being produced.

Patuas have always worked on social aspects that can help society at large.

Interviewer (RN): Okay.

So you have been living in Naya, Pingla.

But do you have relatives from Purba Medinipur? There’s a patua community residing in Purba Medinipur, too.

Anwar Chitrakar: Yes, there’s a patua community at Chandipur.

Interviewer (RN): How is the relationship between the two patua communities?

Anwar Chitrakar: Since the patua community is pretty small, we are all related in some way or the other.

There were relatives with whom we had lost touch.

But now our children have grown up; our other close relatives have grown up too.

They are getting married and that is another way of reviving our contacts with them.

So, in direct or indirect ways, the patuas are all connected.

Interviewer (RN): Is Paschim Medinipur the epicenter of patachitras? Did patuas from Paschim Medinipur migrate here? Or did patuas from Pingla move to Paschim Medinipur and settle down there?

Anwar Chitrakar: It is difficult to pinpoint where exactly it started.

My father used to say that our ancestral home was at Narkel. Danga in 24 Parganas.

He wandered about a lot of places and initially settled down at Thekuachak and then finally here.

So, it’s difficult to say if the patua community at. Nandigram is older or the one at Pingla.

Naya, I think, perhaps came up later.. People from Thekua probably came and settled down here.

Interviewer (RN): Your style of work seems to be a little different from the other artists here.

Can you please dwell on that? What exactly is the style that you are practicing?

Anwar Chitrakar: I took up this art form pretty late.

When I was twelve or thirteen or perhaps fourteen, the market was not that good at that point of time.

Patachitras did not fetch enough money.

My father was the sole breadwinner in the family.

My elder siblings were all involved with this art form.

My elder brother made earthen idols along with my father.

But I left this art form and started doing something completely different.

I bought a sewing machine and started doing all that work.

Much later, perhaps in 1998, I came back again to pursue this art form.

After my marriage, when I took up patachitra, I realized that most of the patuas follow a similar artistic style –

sketching flat lines, filling up with colours, drawing the figures and then outlining them with black.

But my aim was to do something different, since I had started at a much later age.

We would all perhaps be visiting the same customer.

Even if he didn’t buy it, the customer would at least pay more attention to my work thinking that it was a little different from the standard practices.

So, this is the reason why I tried creating a unique style.

I spent a lot of time thinking what exactly I could do.

There was a time whenever we visited Kolkata we would have had to stay back for at least 5-6 days.

Until and unless we had earned earn something, we couldn’t come back home.

It was during one of those times that a gentleman once came up to me and told me about the shadow work of the Kalighat patachitra.

I had absolutely no idea about it.

I had never seen it.

I made a miniature Rajasthani Radha-Krishna image sitting down in the Deshapriya Park and then took the painting to him.

He said that it was not a Kalighat pata.

But I kept insisting that it, indeed, was the Kalighat pata because I knew I had to sell it.

He knew very well that I was wrong.

He told me that I was good at my work and so he suggested that I should go to the Kalighat metro station where I could see the Kalighat patas.

I, accordingly, went to the Kalighat metro station.

I also looked into a few booklets on the subject, which I got from the Indian Museum.

I copied Kalighat paintings quite a number of times and sold them as well.

But then I thought that Kalighat paintings are documents of a certain era.

More or less, we can all understand that they are from the. British period.

But I belong to this generation.

So, I thought I’ll start painting my contemporary times.

Maybe after twenty or fifty years, my paintings, too, will showcase my contemporary society.

That is how I started creating my own artistic style.

I started using the Kalighat shadow work in my own works as well.

Interviewer (RN): So, what is usually the theme of your paintings?

Anwar Chitrakar: My themes range from the zamindari lifestyle to gods and goddesses and also to contemporary social issues.

Interviewer (RN): Coming to your use of colours, how is it different from the use of colours by other patachitrakars/patuas?

Anwar Chitrakar: You see…the colours are all from the same source.

So, it is completely up to individual choice.

The effect of colours depends on how one can put them to use.

For instance, I tend to use pastel shades, and later use a darker shade for the shadow; it becomes more prominent.

So, I prefer sticking to lighter colours.

In all my works, how do I put this across… I mean I try displaying the hand in a somewhat realistic, roundish manner.

Interviewer (RN): Since you said that you had left this art form earlier and took it up much later, were you not interested in this art form as a child?

Anwar Chitrakar: Yes, that is somewhat true.

I had witnessed how even after roaming around displaying his patachitras, my father could at best procure 5-6 kilos of rice at the end of the day.

I knew things could not go on this way.

That is why I had decided that I would engage in a different trade and try improving my family’s financial condition.

Interviewer (RN): Are you willing to train the next generation into becoming patachitrakars/patuas? Do you want the next generation to carry on this tradition?

Anwar Chitrakar: Of course.

As a patua, I definitely want the improvement of our patachitra tradition and to make its own mark in the world.

At one point of time, both my elder sister and I held classes to train the younger generation.

It was usually held on Sundays.

But for some reasons, it got stalled.. We could not continue with them anymore.

But I want my children to learn the art of patachitra.

Interviewer (RN): Let’s come to the aspect of the songs now.

An important part of patachitra is its song.

Did you learn singing as a child, or were you trained by elders?

Anwar Chitrakar: I wasn’t able to learn too many songs from my father as I spent a considerable portion of my life outside home, as I have already mentioned.

Whatever songs I have learnt are mainly from my father.

Later, however, I also learnt a few from my elder siblings.

Interviewer (RN): You have brought about a change in the way patachitra is painted.

Have you also composed songs, accordingly?

Anwar Chitrakar: No.

I’m not that good at composing songs.

Interviewer (RN): In the patachitras based on contemporary social issues, do you think the lyrics of the songs are gradually undergoing a change as well?

Anwar Chitrakar: Yes.

The lyrics are definitely undergoing a change.

They have changed a lot in comparison to the earlier times.

In tandem with the changes in social issues, the language has also undergone change.

We find quite a large number of scrolls which are long.

But then again, there are shorter scrolls as well.

Interviewer (RN): Which one do you prefer painting – the longer scrolls or the shorter ones?

Anwar Chitrakar: It’s not that I don’t paint long scrolls.

However, they are few in number.

I paint shorter scrolls more.

I can show you some of my works later.

I try showcasing contemporary social issues in a single sheet.

Since long scrolls take a lot of time, I tend to paint them less.

Interviewer (RN): Are longer scrolls more expensive? Or does the price depend upon the skill of the artist?

Anwar Chitrakar: It definitely depends on the expertise of the artist – the amount of effort an artist puts in.

Again, a longer scroll would also mean that s/he has to put in greater effort.

But an artist’s fame depends on the kind of work he produces, even if it is on a single sheet.

Interviewer (RN): What are the buyers more interested in? Mythological patachitras or the ones based on a contemporary issue,

or in the different style of patachitra that you are now creating?

Anwar Chitrakar: Earlier, people used to buy patachitras based on mythology because that added to their exotic collections.

There are people who buy long scrolls as memoirs of the past.

Again, there are customers who buy patachitras as wall hangings or showpieces.

Taking that into consideration, it can be said that patachitras on smaller sheets have a higher demand since they add to the beauty of a room.

Interviewer (RN): Are patachitras based on mythology longer? Can patachitras based on contemporary social issues be equally long?

Anwar Chitrakar: It varies according to the story.

It completely depends on the kind of story that the pata is based on.

Interviewer (RN): Which section comprises the buyers of patachitras?

Anwar Chitrakar: That is difficult to pinpoint.

There are all kinds of buyers.

For some people, collecting a piece of an artwork is a matter of great sophistication and pride.

There are some buyers who foresee a bright future for this particular artform.

They believe if they buy ten patachitras now, they’ll be able to resell them after twenty years at double the price.

We have different kinds of buyers.

Interviewer (RN): Are customers displaying an interest in buying longer scrolls or are they buying the single sheet ones?

Anwar Chitrakar: Long scrolls are still being bought.

It is not that long scrolls have lost their market.

There are people who want to preserve the traditional artworks.

They buy these patachitras based on mythology and hang them on walls.

They are spread out evenly on the wall and the remaining portion remains coiled.

When it comes to decorating one’s room, people feel that they can have four short patachitras here, four there.

Interviewer (RN): Are there no stories behind single sheet patachitras?. Do they simply showcase just a scene from normal life?

Anwar Chitrakar: Of course, there is a story.

There is a story behind every art work.

The subject might not be elaborate.

But there is always a story present.

Interviewer (RN): Many patachitrakars follow the Islamic tradition.

How deeply have you embraced the Islamic codes in your social life? Do you observe all the customary practices?

Anwar Chitrakar: We aren’t always able to follow all the rules and edicts.

After working on Hindu gods and goddesses all day long, it is not always possible to follow all the religious edicts.

But we try celebrating Eid, Bakr-i-Eid, Roja – all the major festivals in the Islam tradition.

Interviewer (RN): You have always maintained a harmony, a balance in your practice of religion.

Do you feel that if either of the religious sects starts pressurizing patuas into following solely their traditions,

it would upset this balance? Would that hamper the flow of this art work?

Anwar Chitrakar: Of course, it would.

I personally feel that all religions should be abolished.

But then, nothing can be done.

In this societal set up, we have to follow one religion or the other.

If a certain religious sect, indeed, begins pressurizing people, the worst sufferers would be the patuas.

The Muslims conform to the opinion that patuas are not proper Muslims and Hindus are yet to buy that patuas are Muslims.

Therefore, patuas inhabit such an interstitial position that they would suffer the most.

Interviewer (RN): We have noticed that when a pata is showcased in a fair or an art and handicraft exhibition, it is always the place’s name (Naya, Pingla) that is mentioned.

Do you think somehow, the artist’s name gets effaced, or that for some reason the artist doesn’t get into the limelight?

Anwar Chitrakar: No.

Apart from the place, the name of the artist is also mentioned.

It is no that only the name Pingla comes to light.. I think the name of the artist is also highlighted.

Perhaps, the artist’s name is not always mentioned.

If both the name of the place and the artist can be used, it would be nice.

Interviewer (RN): Is mentioning the name of the individual artist a standard practice? Or is this practice gradually gaining momentum?

Was it there even in the earlier days?

Anwar Chitrakar: Earlier, the individual identity of the artist never got prominence.

In fact, even now, there are many artists who still do not write their names or put their signatures on the patas they have created.

So, this still cannot be considered a common practice but things will change eventually.

Interviewer (RN): Your artistic style is completely different.

Your works are gaining popularity everywhere.

But is your name as an individual artist getting highlighted as well?

Anwar Chitrakar: Absolutely!

Interviewer (RN): A few years back, patachitras began to be based on certain natural calamities, like the tsunami.

What is the story behind it? Why did you choose this as your subject?

Anwar Chitrakar: Whenever a major incident or an accident takes place, patuas try to portray it through the patas.

They have always done this.

Tsunami was a disaster of such great magnitude.

Obviously, a certain pressure would build up in the minds of all the patuas about representing this in their work.

Interviewer (RN): Who was the first patua to have created this pata?

Anwar Chitrakar: I saw my eldest brother Manu Chitrakar create a pata based on the tsunami.

There was a project going on at that time about the tsunami.

To use patuas and their art forms to create awareness about the tsunami and to solicit donations from the common people during the crisis.

It was sanctioned by Mr. Rajeev Sethi from Delhi.

He has done a lot of work with the patuas

On the tsunami.

Let us take the example of the tsunami.

Interviewer (RN): When you start doing a patachitra, do many patuas compose on a single theme at a certain point in time?

Or does the first patua to have started his work gets prominence?

Anwar Chitrakar: I feel that the first person to have worked on tsunami was my brother.

When the project began, many other patuas were involved in this.

A certain attempt was made to give shape to the idea of the tsunami.

None of us had witnessed the tsunami in reality.

So, we would listen to stories from other people in order to get an idea.

That is why, when the project began, many patuas started working together.

Each patua might have done it differently, but that was one instance where many patuas worked together on a single topic.

Interviewer (RN): If, later, at some point of time, a patua creates a patachitra based on a particular social issue or a natural calamity,

would you all join him and collectively create patachitras on the same topic? How would it be portrayed to the world?

Would it be known as a patachitra from Pingla or would it be known by the one who first composed patachitra on that particular theme?

Anwar Chitrakar: Even till this date, I’ve seen my elder brother and sister consulting each other and discussing themes before beginning a pata.

Obviously, when a pata comes into prominence, the name of the individual should be highlighted.

When we follow a similar theme, even if in a different style, we definitely have to acknowledge our source.

Interviewer (RN): How did patachitra begin? Have you heard stories about the origin of patachitrakars/patuas? Do you know how it began?

Anwar Chitrakar: According to what our forefathers said, well…

my elder sister would be able to narrate this better.

Once upon a time, there was a king, a nawab, whose kingdom was plagued by a monster, who would eat up subjects.

When the monster became invincible, a patua came up (at that time they were not known as patuas, though)

and asked the king if he could try his luck against the monster; if he could attempt to kill it.

So, he went up to the hills, and drew a picture of the monster on the rocks.

The monster saw its image from afar and felt challenged; it thought that it was there to impede his movements.

It started fighting with the rock, trying to kill the image.

Eventually, in the process, it got killed.

Peace prevailed in the kingdom.

That is how the journey of the patuas began.

This is what I have heard from my forefathers.

Interviewer (RN): Your art work is quite different.

Are there any particular ones on which you have composed your own song? Would you be able to sing a few lines?

Anwar Chitrakar: No.

There are no songs.

There are only short stories.

There are no songs.

I’ll show few of my artworks based on social issues.

Picture 1: Here are some of my new works.

I’ve tried portraying a scene between a private tutor and a student.

Madam seems to be far more interested in WhatsApp than in teaching.

I’ve tried showing it in my own small way.

The kid is, therefore, a victim of this bad habit since childhood.

Picture 2: Here, I have tried showing how women, across the globe, are scaling great heights, are pioneering great tasks

but still, they are envisioned by some men as their prey.

They are seen as consumable objects.

Picture 3: This is also about female empowerment.

Durga Ma was a woman too.

If she can kill the asura, why can’t another woman do the same?

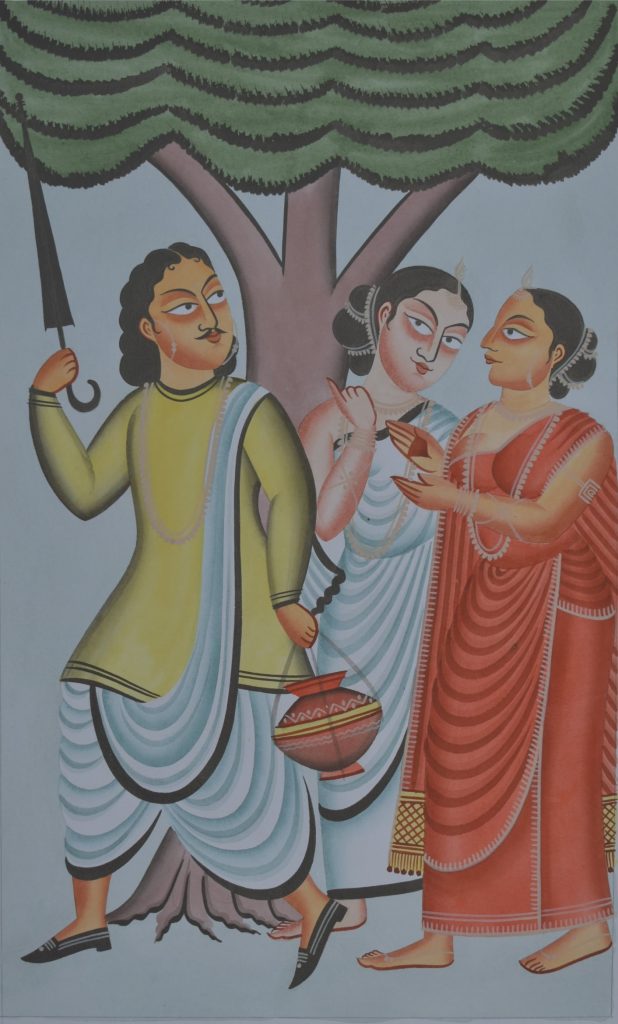

Picture 4: This one is about modern love affairs.

Leaving aside their families, they are eloping with their partners at such tender ages.

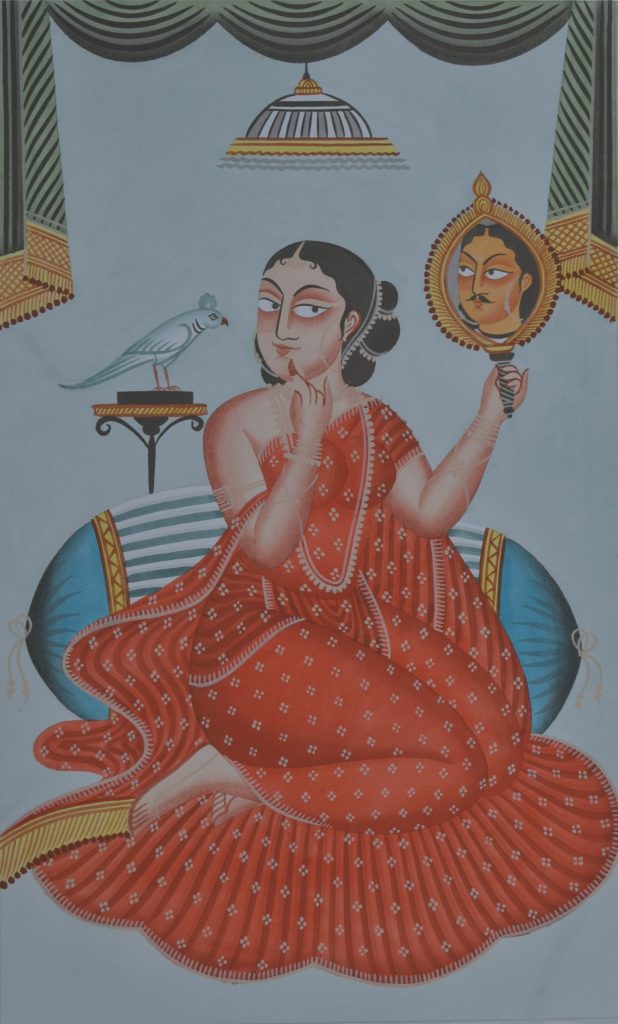

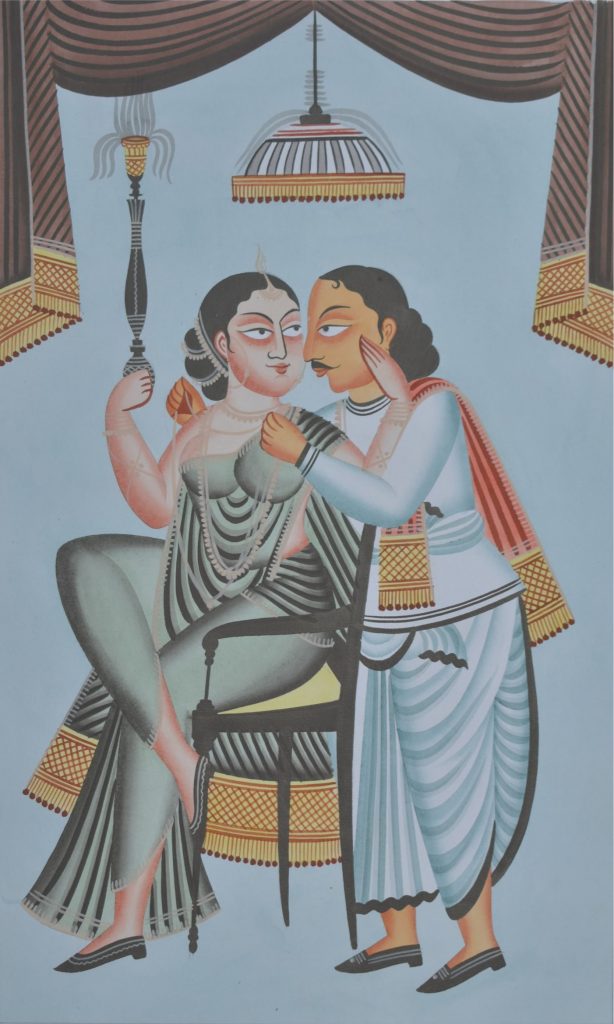

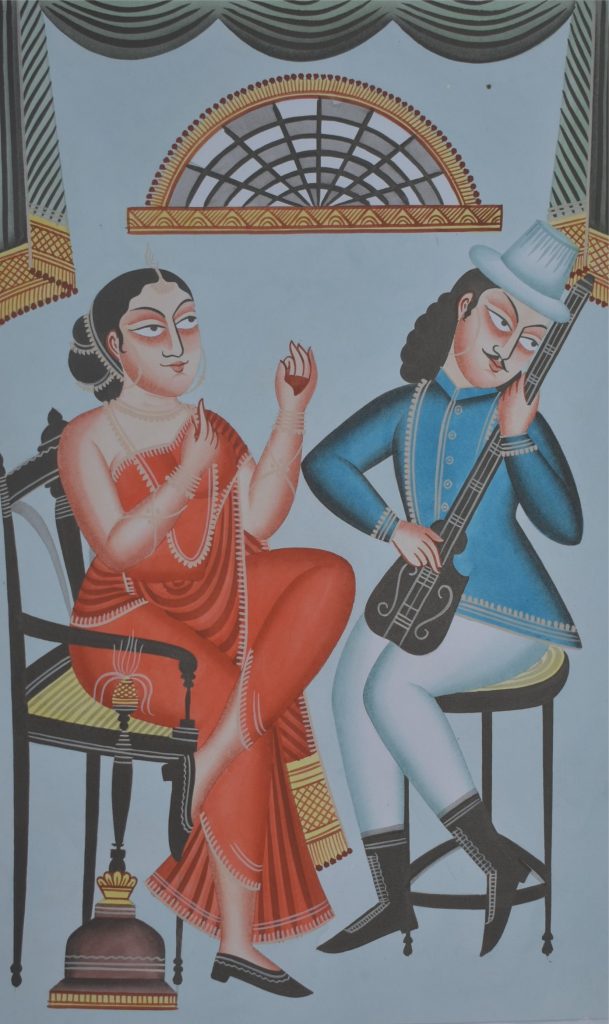

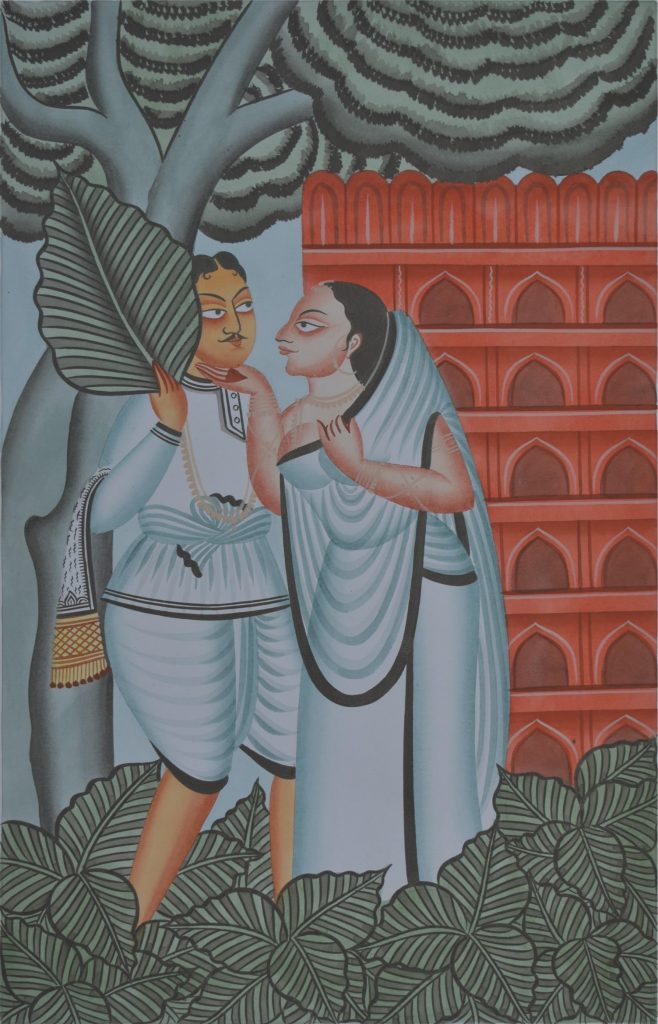

Picture 5: This is Babu and Bibi.

Picture 6: In this I’ve tried portraying the evils of superstitions.

The practice of visiting palmists and asking them to foretell their future has been shown here.

Picture 7: This one is about the unnecessary and careless use of mobile phones.

People are using mobile phones unnecessary when they are on busy roads.

Picture 8: This is about the ill effects of television.

Picture 9: This is a picture of a mother and a son.

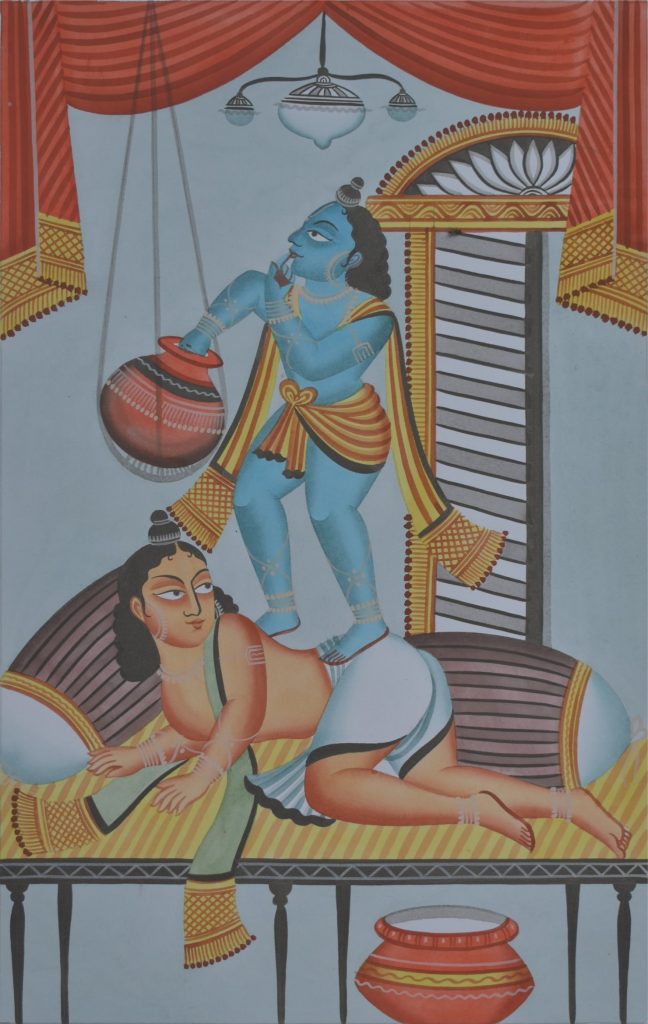

Now, these are all based on mythological episodes.

This is Krishna and Yashoda.

This is Shiva Parvati.

Interviewer (RN): Is this Meerabai?

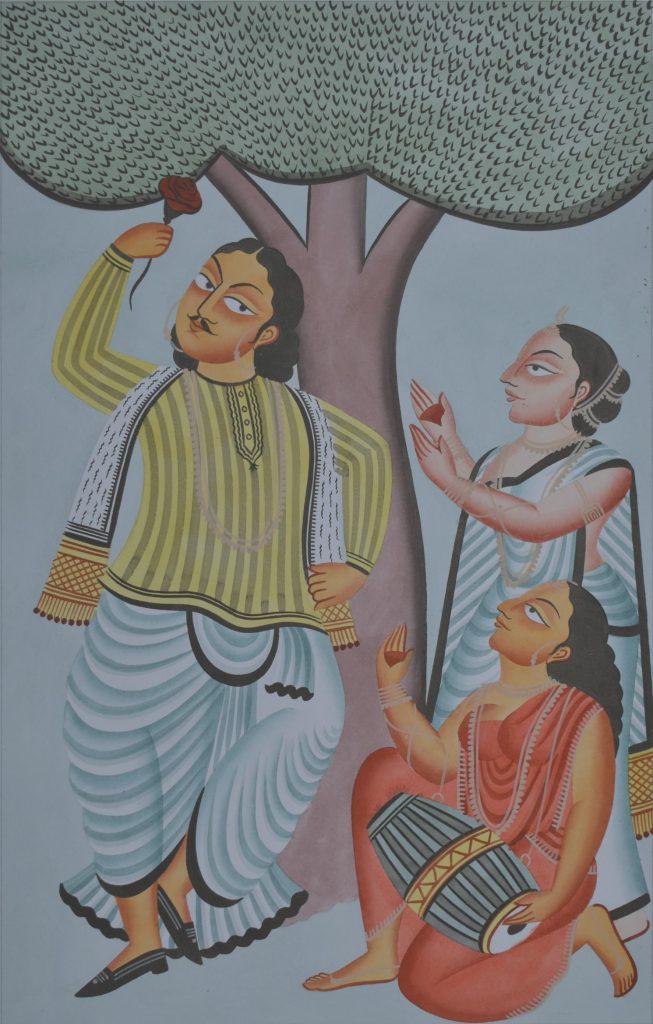

Anwar Chitrakar: This is a character called Golap Sundari, which used to be painted in earlier pictures.

I have adopted that character in my own way.

Here, she’s speaking to a parrot.

Picture 10: This is also about female empowerment.

Apart from this, I’ve also worked on themes like Digital. India, demonetization, Swachh Bharat.

Interviewer (RN): Have they all been sold?

Anwar Chitrakar: No.

There’s an exhibition going on in Delhi from the 11th.

They’ve all been put on display there.

Interviewer (RN): Are you intending to sell these patachitras or are they for display at various exhibitions?

Anwar Chitrakar: Definitely for sale.

Interviewer (RN): I can see that you have put your signature at the bottom of the page.

Is this something practiced by all in the community?. Does everyone put their signature?

Anwar Chitrakar: No.

Interviewer (RN): Not everyone.

In that case, how would their names survive?

Anwar Chitrakar: Actually, many patuas believed that this practice has been followed for generations.

Our predecessors never put their signatures on their patas.

So, why would we? But I personally believe that our predecessors did not create patas with the intention of selling them.

They created patas in order to wander about and display them in villages.

There the individual signatures were not that necessary.

But we are creating patas both with the intention of showcasing and selling them.

So, where is the problem if I put my signature?. The work is, after all, done by me.

Interviewer (RN): (Can you please narrate this in Hindi? They’ll be able to follow, then).

Anwar Chitrakar: Picture 1 on a mobile phone: The food that we are consuming these days are laden with chemicals

so much that in the near future we’ll have to take more medicines than food.

Picture 2 on a mobile phone: People are adulterating milk but are intoxicating themselves and gaining weight.

Picture 3 on a mobile phone: Modern women have outsmarted men in all aspects.

Therefore, men are hiding behind trees.

Picture 4 on a mobile phone: This is the state of the Indian police.

Whenever they see a vehicle, they spread their caps and demand money.

This is a bus from where the conductor just spat betel on the police’s cap.

Picture 5 on a mobile phone: He is hammering the heads of all the children.

The children only believe that all knowledge lies only in the realm of television.

Picture 6 on a mobile phone: This is the one on selfies.

Interviewer (RN): Are you on social media like Facebook and all?

Anwar Chitrakar: I am not on Facebook.

Interviewer (RN): How do you observe the social problems of the young generation, then?

Anwar Chitrakar: We portray these through our paintings and put them on display in exhibitions.

Interviewer (RN): Yes.

But how do you get to know about these problems that are plaguing the world.

Anwar Chitrakar: Through television, newspapers.

I am not on Facebook because I don’t find anything fruitful on Facebook.

There are so many unnecessary things cluttering Facebook that the entire purpose of having a Facebook account has changed.

Interviewer (RN): So, basically television and newspaper act as your gateway to the world.

Anwar Chitrakar: Yes.

You may say that.

Apart from that, we keep travelling to different places, witnessing various things; these are the experiences that get portrayed in my patachitra.