Transcript

Interviewer: What is your name?

Amit Chitrakar: My name is Amit Chitrakar.

Interviewer: How long have you been living here?

Amit Chitrakar: I was born and brought up here. I am forty-five years old now.

Interviewer: Was your father, too, a local resident of Naya?

Amit Chitrakar: No, my father was from Chaitanyapur, PurbaMedinipur. It is fifty-five years since he moved to this place.

Interviewer: How long has the patua community been livinghere?

Amit Chitrakar: They have been living here since the last ninety- to ninety-five years. I have seen my father movehere and he is almost seventy-two or seventy-three years old now. I have myself seen patachitra being practised since then. Back in those times, patachitra was practised on a smaller scale. It has increased by leaps and bounds now.

Interviewer: So, are both your parents alive?

Amit Chitrakar: Yes.

Interviewer: Who was the eldest member in your patua community to have settled down here?

Amit Chitrakar: Jyoti Chitrakar, Dukhushyam Chitrakar, Gokul Chitrakar are the eldest members of the community whom I am aware of.

Interviewer: Did both your father and grandfather live here?

Amit Chitrakar: No, my grandfather was from Chaitanyapur.

Interviewer: Okay. So, your grandfather never came here.

Amit Chitrakar: No, he didn’t.

Interviewer: Does your father still practise patachitra?

Amit Chitrakar: Earlier, my father used to make clay idols. He used to create idols of gods and goddessesand also made clay figurines. He started working on patachitra only after he came to Naya.

Interviewer: Did your grandfather never practise patachitra?

Amit Chitrakar: He was, but not that frequently. He, too, used to make clay idols. But sometimes he painted patachitra as well. But, at Chaitanyapur, the practice of patachitra was not that prevalent.

Interviewer: Why did your father move out from Chaitanyapur and start living here?

Amit Chitrakar: My father had to struggle a lot in his initial days. He used to work as an unskilled labourer, was engaged in quarrying and similar work. Things improved gradually.

Interviewer: There are some patuas in PurbaMedinipur as well. Do you have any connections or relations with them?

Amit Chitrakar: We have relatives in PurbaMedinipur. So, yes we have connections with them.

Interviewer: Did patuas migrate from PurbaMedinipurto Naya or was it vice versa?

Amit Chitrakar: Patachitra is more prevalent here. However, patuas from PurbaMedinipur visit Naya often. We visit them too. There are certain elderlypatuas like NiranjanChitrakar.

Interviewer: Who are the indigenous patuas – the ones living in Purba Medinipur or the ones from Naya?

Amit Chitrakar: They are present in both Purba Medinipur and Naya.

Interviewer: Do you see any difference between the number of patuas who were there earlier and the number of patuas who are there now? Has the number increased?

Amit Chitrakar: The number of patuas has increased a lot.

Interviewer: What do you think is the reason behind this huge increase?

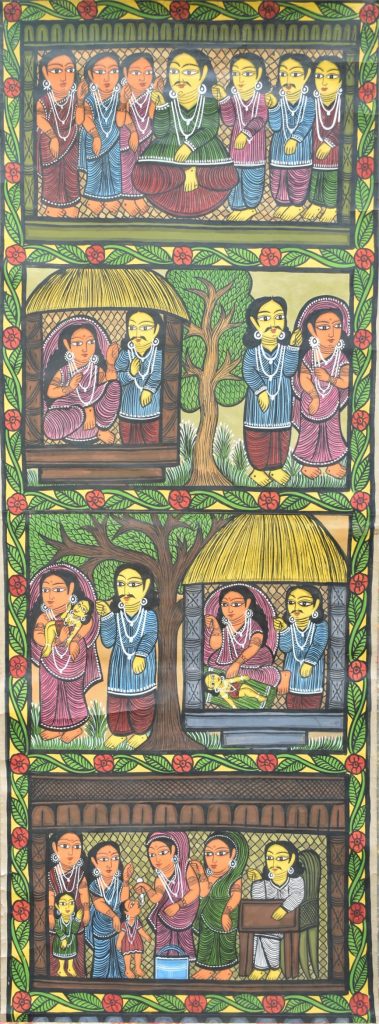

Amit: Actually, Banglanatak.com played a huge role in this. They helped us connect to an NGO. That is when the work in this area started proliferating. They did a lot of work. They trained us how to sing pata songs. The ones who didn’t practise patachitra earlier also started working on it.

Interviewer: The population has increased considerably. Does that mean that there might be families living here whose forefathers were not perhaps patuas? Are there people who became patuas only after they moved to Naya?

Amit: Yes. There are some people from the neighbouring areas who want to learn patachitra. In fact, some of them came to Bahadur Chitrakar and learnt how to make a pata. There’s one such person who is doing a pretty good job. His nickname is Bagha. I don’t know if he has any other name. Oh yes, he is also called Gangamana.

Interviewer: Why do you think these people are getting attracted towards patachitra? Is it because of the money that it generates, progress that they think they’ll be able to make, or is it out of a deep-rooted interest in this art form?

Amit: It is true that patachitra, nowadays, is generating a much higher income than earlier. But of course, they are joining us because they like this art form. Only an eager and enthusiastic person, who is willing to learn patachitra would want to join. Some people have that curiosity, that eagerness. Anyone who wants to be a good artist would have that quality.

Interviewer: How is the financial condition of patuas these days? How was it earlier? How did your father, for instance, meet his expenses?

Amit: Earlier, we had to struggle a lot. We are better off now. We had to work extremely hard back then. Nowadays, we are engaged in making patachitras. Several fairs are being held. Our patas are gettimg sold. Some customers also come down to Naya to buy patas.

Interviewer: Was your father associated with patachitra, or with selling patas?

Amit: No, initially he was not. Gradually he saw that people around him were working on patachitra. It appealed to him. That is when he started painting.

Interviewer: How was the life of patuas in earlier times? What kind of a financial condition did they live in?

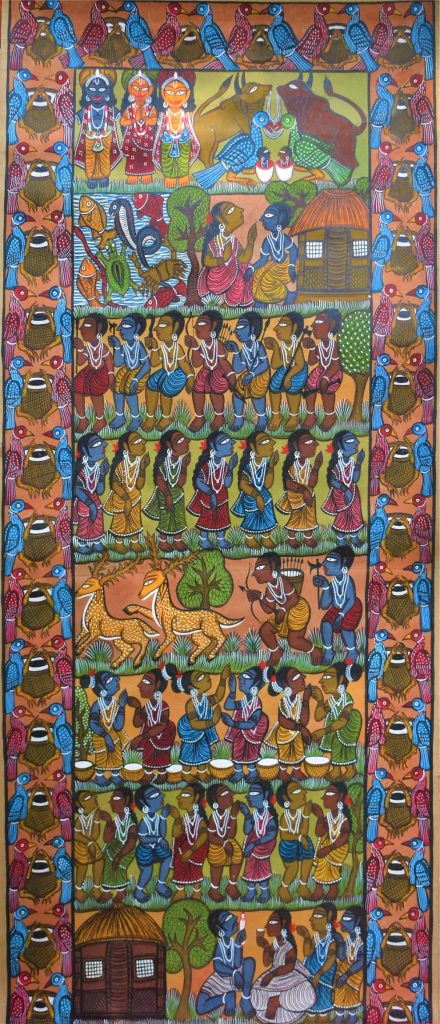

Amit: Earlier, patuas used to roam about villages, displaying patas, singing songs. They would get just a handful of rice. Their families would wait for them till evening to bring that rice so that theycould cook and have something to eat. The lives of the earlier patuas reeled under abject poverty.

Interviewer: When your father started painting, what were usually the themes he worked on?

Amit: My father used to make idols of gods and goddesses. It has only been thirty years perhaps since he started doing patachitra. He began working on this only after moving to Naya.

Interviewer: Okay. What were the common themes?

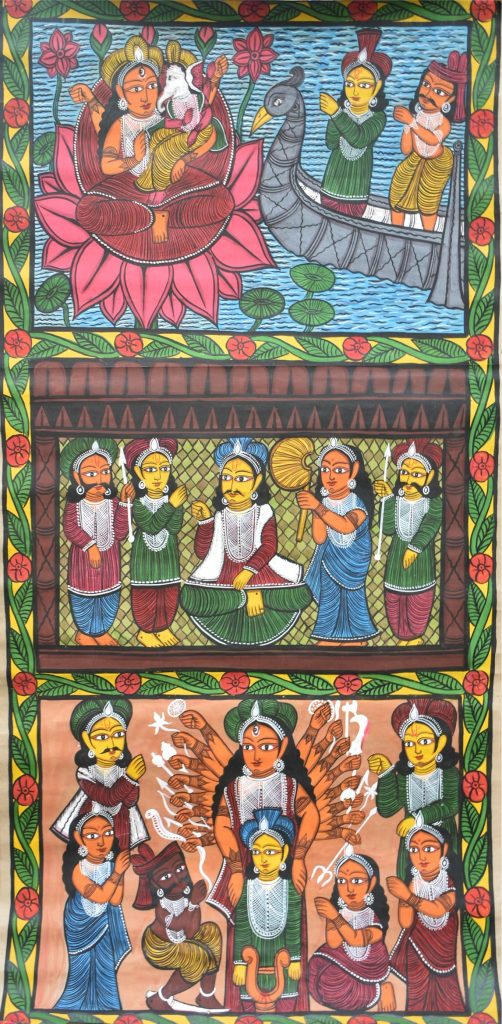

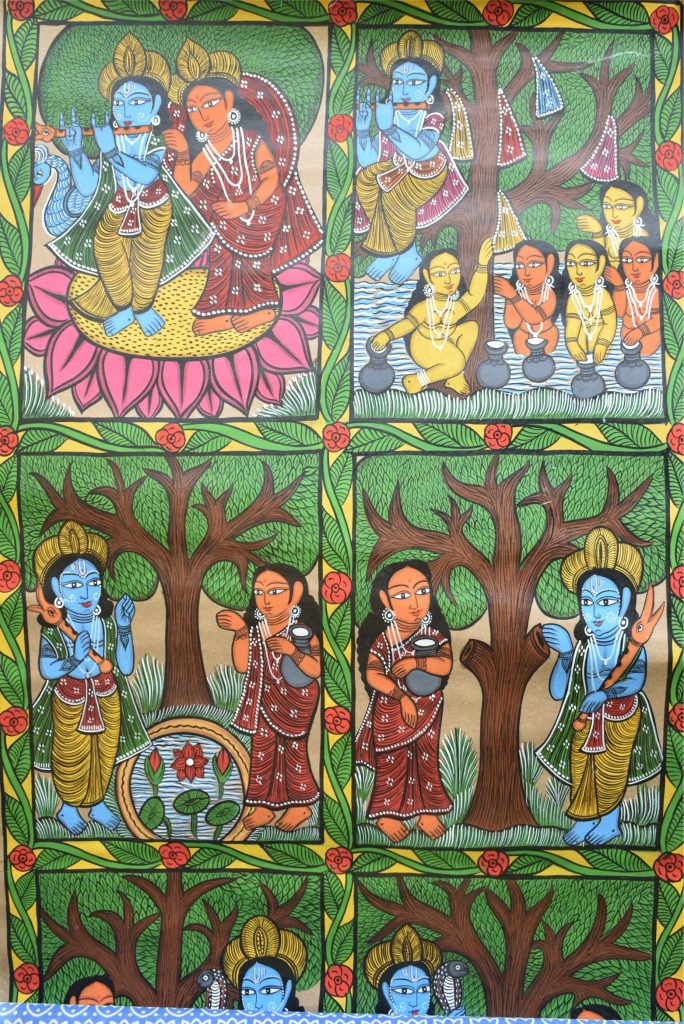

Amit: He usually painted on the Ramayana or the goddess Durga, or maybe a social issue like afforestation.

Interviewer: Did he paint on both mythological and contemporary social issues?

Amit: Yes. He painted both.

Interviewer: How different are your patas from the patas that your father used to make back in those times?

Amit: Their work was definitely very good. The patas were pretty different then. Nowadys, you’ll find so many new designs. Now there’s a constant urge to modify the designs further and create something unique. The earlier patuas maintained the tradition which their predecessors followed. But we continuously strive to bring novelty in our work.

Interviewer: Do you also paint on mythological themes?

Amit: I paint on both mythological and social issues.

Interviewer: You said that you are trying to alter a few things, trying to incorporate a few new elements. Could you kindly elucidate on that?

Amit: Talking about bringing in changes, I keep changing designs. For instance, while working on a sari, I’ll keep pondering on how it would look if a certain design was narrowed down, or moved to the border, etc.

Interviewer: Nowadays, you don’t work only on scrolls. As I can see, you are making patachitras on various other things, including saris. Did this practice of painting on saris exist before as well?

Amit: No, not at all. As far as I have observed, patuas used to paint on fine pieces of paper. Then they started using slightly thicker paper – what is called art paper. Now they have begun painting on cloth. We have realised that saris too can be painted, as it looks good. Also, patachitras are being painted on the canvas of the puja pandals. This is how patachitra is gradually being adapted into various media.

Interviewer: Could you please tell us something about pata songs? Did your father compose songs was well?

Amit: No, my father didn’t sing too many songs. He knew a few. My father’s maternal uncle, I mean my grandfather knew many songs. My father learnt these only after he came here. DukhushyamChitrakar and GurupadaChitrakar are the ones who compose pata songs. We all learn from them. We don’t compose songs ourselves. They do. We just pick up the songs from them.

Interviewer: Have you noted any difference between the lyrics of the pata songs back then and the lyrics of the songs composed now? Has there been any revision in the lyrics of the songs? Or is it still the same?

Amit: The tune has changed. The tune has been changed so as tobe made even more appealing.

Interviewer: What about the lyrics, the language?

Amkit: The lyrics have changed.

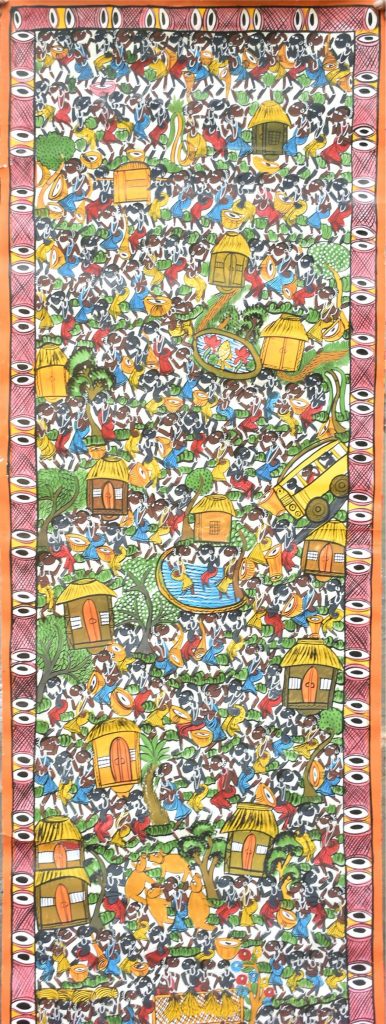

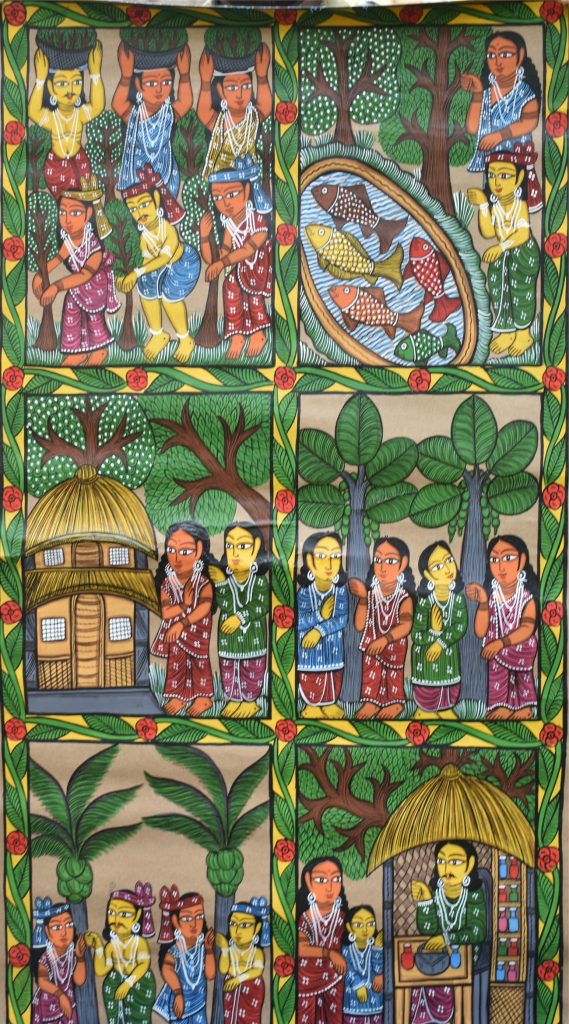

Interviewer: There are two kinds of patachitras – long scrolls and short square ones. Which of these patas were made in earlier days?

Amit: Earlier, only long scrolls were made. The entire story was narrated through the scroll. But nowadays, small, square patas are made because of space crunch. People cannot hang those long scrolls. These days, we have small houses. So, where would someone hang those scrolls? That is why small patas are made these days.

Interviewer: Which ones do customers prefer- the long scrolls or the small square ones?

Amit: Usually the smaller ones, ranging from two feet to five feet. The size usually doesn’t exceed five feet.

Interviewer: How do you decide upon the price of the patas? Is it determined by the length of the scroll or by the quality of the work?

Amit: Definitely the one with detailed work fetches a higher price. It’s not the length that matters, but the quality of work. But then, long scrolls obviously have more work. So, automatically the price goes higher.

Interviewer: Which pata does the customer prefer – the ones based on mythological stories or the ones dealing with contemporary, social issues?

Amit: Customers generally prefer small square patas based on social issues so that they can decorate their houses. However, the demand for patas based on mythological stories is also there. But the inclination for patas based on social affairs is somewhat more.

Interviewer: Do you start teaching patachitra to all the children right from a tender age?

Amit: There’s no need to teach them separately. They learn these by themselves. For instance, even if they are studying, they watch us work and observe the art. They learn things that way. A sense of eagerness gets kindled. They feel that if their parents can work so can they. This is how they learn.

Interviewer: Now that they are learning patachitra, what would you like them to do – carry on with this tradition of patachitra or would you encourage them to choose a profession that they want?

Amit: We sincerely want them to hold on to the tradition like we did.

Interviewer: But if someone aspires to choose a different path… for instance, if someone wants to opt for higher education, or choose a different way of life, what would you do then?

Amit: I don’t think anyone has risen to a level yet where one cango in for higher education and get a white-collar job. Have you met anyone in this entire community with a job? You won’t find anyone.

Interviewer: On an average, how educated are the children?

Amit: Well… upto the twelfth standard. No, actually there are some who have got admitted to colleges. That’s it.

Interviewer: How many children have gone to colleges so far?

Amit: They got admitted to colleges and then the girls got married. This is the common practice.

Interviewer: What about the boys?

Amit: My brother got enrolled in a college. But even he quit studying. Just one or two people make it till that level.

Interviewer: Are you all Muslims?

Amit: Yes, we are all Muslims.

Interviewer: Okay. But then, you have a Hindu name. What is the story behind this?

Amit: Actually, it’s about what your parents named you. There’s no separate Hindu-Muslim issue involved here. When someone hears the name for the first time, s/he might think that I am a Hindu. But I don’t have any issue regarding my name. But kids these days have Muslim names.

Interviewer: Is there any reason why your generation had names that sounded more Hindu-like?

Amit: My parents had named me so maybe because they had Hindu acquaintances, and they painted images of Hindu deities. Perhaps, it was because of the connection they shared with the Hindus that they gave me such a name.

Interviewer: Do you paint only on Hindu mythological stories? Or do you portray Muslim stories as well?

Amit: We work mostly on Hindu mythological stories. There are depictions of Muslim stories as well like the pata on Satya Pir. But that is pretty rare. We have just two Muslim narratives. Patachitras are, by and large, based on Hindu stories.

Interviewer: While coming to this place, we noticed a Shiva temple. What could possibly be the reason to establish a temple? Are there Hindus residing in this area as well?

Amit: Where did you find the Shiva Mandir?

Interviewer: It was there near Bahadur Chitrakar’s place.

Amit: Where is the Shiva temple there?Are you talking about the Hari temple? Oh! That’s a Hindu neighbourhood and, therefore, they have that temple.

Interviewer: Is that completely a Hindu neighbourhood?

Amit: That side of the locality is where Hindus live. I mean, a few Hindus, who had migrated from Maitipara have been staying there. They had land here; so they settled down there. Adjacent to that, we have Berapara, yet another Hindu locality. But we are on friendly terms. Whenever there’s an occasion, we invite each other to our respective communities.

Interviewer: Do you follow all the religious customs? Do you get time to observe them?

Amit: Yes. We are Muslims. So, we have to follow all the customs. We have tochant the azaan, offer prayers regularly. We followour religion, but then again, whenat work, we have to focus just on that.

Interviewer: Suppose, someone from a higher rung dictates that you have to spend your life strictly according to what is mentioned in the Islamic codes, what would your reaction be?

Amit: Well… I don’t think anyone would ask us to alter our lives drastically because of our religion. Yes, we work on Hindu narratives. But that’s a different thing altogether. Hopefully, no such pressure would ever be built. And if that happens, it would turn out to be a huge event. There’s no point discussing this. One thing that I must admit is that Hindusand Muslims live peacefully. There’s no communal tension between the two communities. We observe our faith, they observe theirs. At least for the time being, there’s no issue amongst us. I don’t know what the future holds.

Interviewer: Could you please tell us if several patuas get involved in creating a instance, when a patachitra is being exhibited in a fair, or is being displayed at an exhibition, would it be labelled as a common work of art by all the patuas from Naya, or would it be known by its individual creator?

Amit: It is known by the name of its individual creator. If someone has painted it, why would his individual name not be mentioned? For example, if Bahadur paints a pata, it would bear his name. Again, if I paint a pata, it would have my name.

Interviewer: But usually, we don’t get to hear individual names. The artist doesn’t get his share of the limelight. It is usually known as a collective enterprise. For example, it might be known as a pata from the Naya village, or perhaps as a collective effort by a certain group. Have you ever reflected on that?

Amit: If patuas decide to present as a team, they would collect patas from individual artists and submit as a group. Names of the artists are usually mentioned. But if they do not submit the names, in that case, people won’t be able to understand who made the paintings. This happens at times.

Interviewer: So, you want the individual artist’s name to be mentioned and you think that is good?

Amit: Of course, it is. If I am working on a pata, my name should be mentioned. Otherwise, how would people get to know who made the picture? If I submit all my works anonymously, what would I gain from it? It would be my loss.

Interviewer: When customers are buying patas, do you think that they are buying them with the full knowledge as to who has made the pata? Or are they buying them as a collective enterprise of a certain community.

Amit: Usually, a pata is known by the place it comes from. For instance, if a pata is from Pingla, PaschimMedinipur, it will be known by the same. The names should be mentioned. Otherwise, if someone mentions that this is a pata from Pingla, then how would people identify the artist?

Interviewer: Talking about the patas on social issues or natural calamities like the Tsunami…do you think that the original creator was duly acknowledged or was the Tsunami pata better known as a collective endeavour?

Amit: Suppose, two patuas have composed patas on the Tsunami. Following them, others, too can start painting on the same topic. But what is important is who composed the song. I can’t claim that I have composed that song.

Interviewer: Is the number of patuas who can compose songsmuch less in comparison to the number of patuas who can paint?

Amit: There are around eight to ten patuas who can compose songs.

Interviewer: Are they all elderly people? Or do you have younger people composing as well?

Amit: We have a few young people as well.

Interviewer: Where do they learn these pata songs from? Are they taught?

Amit: Yes, when we have workshops, we are trained to compose pata songs. But then, the individual, too, has to try on his own. Else, he won’t be able to compose. He should be able to weave magic using his words. Otherwise, anyone could have been a composer.

Interviewer: Who was the first patua to have created a patachitra on the tsunami? Whose idea was it to paint on this theme, and garner acclaim?

Amit: It was DukhushyamChitrakar and GurupadaChitrakar’s idea. There’s a person called Rajeev Seth, from Delhi. You must have already heard his namebeing mentioned. He bought several patas on that theme. So, many of us had made patachitras on the tsunami at that time and sent it to him. That is when they painted, composed songs and went to Delhi along with a few others. They were able to sell quite a few patas.

Interviewer: Which was the first pata that you had painted?

Amit: The first pata that I had painted is not with me. It is there with Bahadur Chitrakar. He has displayed it in his museum. He has displayed the paintings of several other patuas as well. But he has mentioned the individual names of the artists. I don’t have my paintings because I have sold them all. The only work that I have is with Bahadur. He has preserved it.

Interviewer: What was the patachitra about?

Amit: It was about the abduction of Sita.

Interviewer: How did the tradition of patachitra begin? Could you please let us know aboutits origins?

Amit: Did people work on patachitra in Akupur? I think it originated in Akupur and then spread to these parts. I won’t be able to shed much light on that. Bahadur Chitrakar would be able to answer that because he has travelled a lot. I haven’t travelled that much.

Interviewer: Have you heard any story from your elders about this?

Amit: Obviously there are stories behind the origins of patachitra.

Interviewer: Could you kindly tell us a little about that?

Amit: Patachitra existed even in Bihar. I won’t be able to say much because I haven’t travelled that widely. There’s no point lying. I’ll only be able to tell you what I know.

Interviewer: If you could kindly tell us whatever you have heard, or whatever you know.

Bahadur: Earlier, people used to go hunting. So, in order to keep a count of the number of people who went out hunting, their images were painted on the walls of the caves. They used to keep track of how many women, how many children had stepped out. That was how patachitra began. Primitive men and women used to carve onthe walls of the caves with stones. Vegetable dyes did not exist back then. That is how they kept track of how many people went out for hunting and how many didn’t come back. Patachitra basically began from cave paintings. This is a story that I have heard from my parents. The Hindu god Vishwakarma had given a boon from which seven children were born like Kumbhakar, Malakar, Swarnakar. We, the patachitrakars are one of them. Patachitra is ancient. From what has been found in various jungles, in caves, we come to the conclusion that patachitra is indeed ancient.

Amit sings a pata on afforestation:

Ladies and gentleman… kindly plant trees.

Trees help us in various ways. It prevents soil erosion.

Ladies and gentleman… kindly plant trees.

If you plant trees by the banks of ponds, the number of fishes would proliferate.

Trees prevent soil erosion.

Ladies and gentleman… kindly plant trees.

We are benefited by palm trees. We can make palm candies from them.

The benefits are limitless.

Ladies and gentleman… kindly plant trees.

Interviewer: What is this pata about?

Amit: This revolves around Krishnaleela.

Interviewer: Is this the one that depicts the scene where Radha goes to fetch a pot of water and is followed by Krishna?

Amit: Yes.

Interviewer: What we noticed was that several patuas are painting the same patas, singing the same songs.

Amit: It won’t be the same. It would be similar. For example, some would sing solo songs while others would sing in chorus.

Interviewer: Do you all follow just one song?

Amit: Yes, we have a single son, with several variations because each individual would bring in minor changes in the tune.

Interviewer: Okay, so the lyrics are the same. The only difference is in the tune.

Bahadur: Yes, these songs have been handed down by our forefathers. They are sacrosanct. So, we don’t meddle with the lyrics. The difference is only in the tune because not everyone is gifted with a melodious voice. For instance, we all might be able to write but our handwritings are not the same. Similarly, God has blessed each of us with different voice qualities.

Amit: Yes, some can sing well while others cannot.

Bahadur: So, for the mythological patas, we have a single song, which we all follow. It’s different for the patas based on the social, contemporary events.

I can’t sing well. My brother’s voice quality, however, is really good. I have to face a lot of problems because of that.